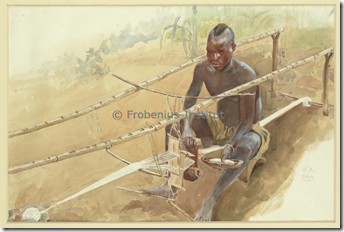

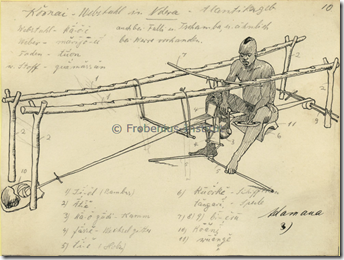

From the image archive of the Frobenius Institute in Frankfurt, three views of a Koma weaver in the Atlantika mountains (then part of the German colony of Kamerun, now in Adamawa State in Nigeria, near the Cameroon border.) the watercolour above, dating from 1911, is by Carl Arriens, while the photo and sketch below are by the great German ethnographer Leo Frobenius.

Friday, 16 January 2015

Monday, 23 April 2012

Dogon country, Mali, 2010

Dogon weaver in the village of Aouguine, Mali, September 2010.

Koro Guindo spinning cotton thread, Aouguine, Mali, September 2010.

Both photographs copyright Huib Blom. Please do not reproduce without permission from Huib who can be reached at his site www.dogon-lobi.ch where you can also order his remarkable book of photographs.

For an important discussion of the rather controversial topic of Dogon weaving see Bernhard Gardi’s recent contribution to the French exhibition catalogue Dogon by Hélène Leloup (Somogy, 2011).

Thursday, 23 February 2012

Sierra Leone Heritage resources site online

“The SierraLeoneHeritage.org digital resource is the main output of a research project entitled ‘Reanimating Cultural Heritage: Digital Repatriation, Knowledge Networks and Civil Society Strengthening in Post-Conflict Sierra Leone’. The project is being funded by the UK’s Arts and Humanities Research Council as part of its Beyond Text programme and is being directed by Dr Paul Basu of University College London. The project’s Informatics team is being led by Dr Martin White of the University of Sussex.

The ‘Reanimating Cultural Heritage’ project is concerned with innovating digital curatorship in relation to Sierra Leonean collections dispersed in the global museumscape. Building on research in anthropology, museum studies, informatics and beyond, the project considers how objects that have become isolated from the oral and performative contexts that originally animated them can be reanimated in digital space alongside associated images, video clips, sounds, texts and other media, and thereby be given new life. At the project’s heart is a series of collaborations between museums including the Sierra Leone National Museum, the British Museum,Brighton Museum and Art Gallery, Glasgow Museums, the World Museum Liverpool, and the British Library Sound Archive. The project has also engaged in capacity building activities in the cultural sector in Sierra Leone and has commissioned the production of videos on cultural heritage themes from Sierra Leonean partner organisations including Ballanta Academy of Music, iEARN-Sierra Leone, and Talking Drum Studios.

Another key objective of the project has been to integrate web-based social networking technologies into the digital heritage resource in order to (re)connect objects in museum collections with disparate communities and to foster reciprocal knowledge exchange across boundaries. Visitors to SierraLeoneHeritage.org can thus become part of its community, contribute comments, engage in discussions, and upload their own images and videos.

Historically, cultural heritage has been a low priority in Sierra Leone. The hope is that by reanimating these dispersed collections and the differently-situated knowledges that surround them, Sierra Leone’s rich cultural heritage can be better appreciated and contribute to the reanimation of Sierra Leonean society more generally.

For more information please contact info@sierraleoneheritage.org “

Of particular interest to this site is the wonderful collection of videos, including a good explanation of tripod loom weaving. Also searching for “textiles” or “costume” brings up images of the majority of Sierra Leone country cloths in UK museum collections (although not unfortunately the important group at the Horniman Museum, London.) The pictures are too small but at least it gives a glimpse of the collections online, some for the first time.

Monday, 20 February 2012

Exploring form and colour – An Ewe textile masterpiece

The large elaborately patterned cloths commissioned from master weavers by chiefs and wealthy “big men” of the Ewe in the Volta region of Ghana and Togo in the early decades of the C20th are some of the most admired and sought after of African textiles. There was far greater diversity of design and elaboration of technique among the weavers that made up what we now regard as the Ewe tradition than among the court-centred kente cloth weavers of their near neighbours, the Asante. In simple terms Ewe cloths were prestige display items worn at important events to demonstrate publicly the wealth and cultural sophistication of the wearer. Since elaboration of well woven figurative weft float motifs such as people, animals, swords etc was the primary factor in the increasing the cost of a cloth ( as they required more skill, time and costly materials to weave) in the majority of cases they provided the primary signifier of the owner’s wealth and the weaver’s skill. From time to time, however, we can encounter a cloth where a more subtle display of skill and connoisseurship is apparent . Such is the case with the cloth above, dating from circa 1920-40, (click the image for a much larger view) which, in my view at least, is a tour de force of weaving skill expressed through variation in colour and form rather than in complexity of motif.

The warp pattern (going vertically on the detail image above) remains the same throughout the cloth – blue predominates, broken up by clusters of narrow stripes in red, white, and yellow. Sparing use is made of weft stripes, in the section above, a pair of wider stripes in yellow thread. Three of the warp colours, red, white, and blue, along with another colour, green, are used widely in the weft patterning, while the forth warp colour, yellow, appears much less.

The detail above also introduces us to the main decorative technique explored to such effect on this cloth, a continual reconfiguration of width and colour and placement in the use of weft faced stripes. The weaver uses the basic pattern structure of many Ewe cloths, in which a composite pattern block is made up of two wide weft faced blocks that frame a warp faced section with a central motif. This composite pattern block is then aligned against warp faced areas on the two adjacent strips creating an alternation that structures the overall pattern layout of the cloth. Unusually the weaver also adds paired weft stripes (not weft-faced stripes) that break up many of the warp faced blocks, varying this in places by omitting them or using a different colour or technique.

Within this grid structure the weaver plays around with variations in the width of stripes and the placement of colours, restraining his palette to red, blue, white and green, with sporadic yellow. Variation is also achieved by plying two colours of thread together, in the section above blue with white, red with white and green with white.

If we focus on a a single strip this use of stripes emerges clearly – click the image to enlarge. Each of the nine composite pattern blocks differs from its neighbours. Reading from the left we have: 1 – a double stripe in red and white, single red, single white, plied red and white; 2 – two wide blocks composed of narrow red, white, blue , and plied red/white, framing a single wide plied red/white stripe; 3 – two wide blocks of varying width stripes adding green to the previous colours, with the same central stripe; 4 – as 3 but with central stripe omitted; 5 – returns to 3 with central stripe but slight variant in second block; 6 – block made up of ten evenly spaced narrow stripes separated by warp faced areas; 7 – the first three narrow stripes of the previous block are compressed together, a zigzag supplementary warp float motif (one of only two on the entire cloth) separates others; 8 – two blocks composed of varying stripe widths, no central stripe; 9 – as 8 but with red/white plied central stripe.

Finally, if we return to the full picture from the start of the post we see a distinct lower edge strip in which solid wide stripes, some framed by narrow white stripes, simplify the pattern block layout.

What interests me here, aside from the visual beauty of the result, is how a master weaver could set himself constraints in colour and pattern, using only part of the repertoire at his disposal, and using rhythms of repetition and variation, explore those possibilities to the full. Close attention to the cloth pays tribute to his skill and to the knowledgeable patronage of his customer.

To view this cloth and others in our recently updated gallery of Ewe textiles click here. Or of course you are welcome to come and see it at our shop.

Thursday, 17 September 2009

Weavers in African Sculpture

The Sogo bo (literally "the animals come out") puppet theatre tradition of the Bamana people of Mali embraces a huge range of characters and performance styles, from larger than life animal masquerades animated by several men, to small string puppets. Inspired by a visit I made to a puppet festival in Markala, Mali last year I asked if there were any puppet depictions of weavers. Recently I received these two charming sculptures which now decorate my shop.

Another puppet by the same sculptor.

Both these puppets are the work of a man known as Dina Ballo from the village of Zambougou, whose is said to be the only Sogo bo sculptor who makes weavers. Sculptural depictions of weavers are surprisingly rare despite the activity being an everyday sight in many parts of West Africa. Looking through my library I found only two further examples, shown below.

An asen is an ancestral altar from southern part of the Benin Republic. This image is taken from the recent and excellent book Asen, Ancestors, and Vodun by Edna G. Bay (University of Illinois Press, 2008)

This remarkable ifa divination bowl (Yoruba, Nigeria) from the Ethnography Museum, Berlin, depicts a woman weaver on the upright single heddle loom (Photo from Brigitte Menzel, Textilien Aus Westafrika, Museum fur Volkerkunde, 1972)