“Written descriptions of looms, weaving technologies, and their histories often prove difficult for both author and reader.” Doran Ross. 1998. Wrapped in Pride: Ghanian Kente and African American Identity. UCLA Fowler Museum of Cultural History. p.75

These three motifs (figs.1-3) from an arkilla kunta-blanket are of outstanding finesse, quality and of a certain age. The vegetable colours have not faded and match very well, the yarn had been finely spun with great regularity. As arkilla kunta-blankets are very rare, their ethno-historical background is of interest.

The arkilla kunta is the old form of the better known arkilla kerka woven by the maabuube, the weavers of the Peul in Mali. Something like 200 years ago two groups of people left the Upper Delta of the river Niger in c0entral Mali and eventually settled down south of Gao in today’s Republic of Niger. These two small groups are known as Kurtey and Wogo. Their language is Songhay. The Kurtey claim their descent from the Peul, the Wogo see their mythical origin in a small place called Tindirma south west of Tombouctou.

Among other Malian traditions, the Wogo kept a specific symbol for their marriages until the early 1960s, namely this huge tent-like blanket kunta being completely woven with sheep wool. Not so the Kurtey; they had no such arkilla-blankets.

Literally, arkilla has an Arabic root meaning ‘mosquito net’.

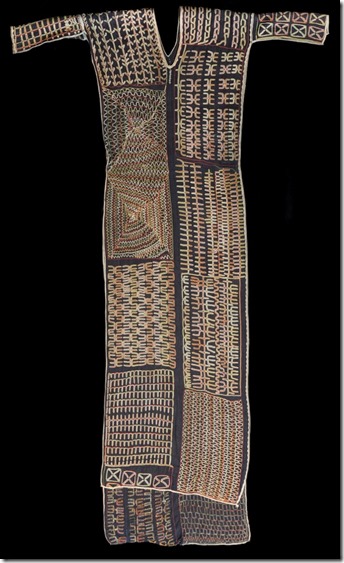

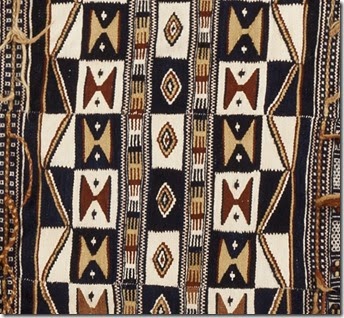

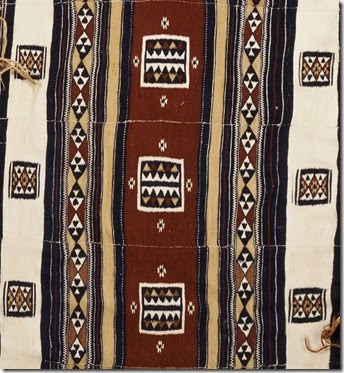

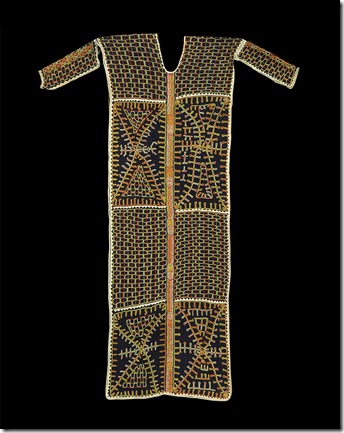

There are significant differences between an arkilla kunta and an arkilla kerka. A complete kunta should have five rather wide strips (32 cm), the fifth or lowest one being simpler woven than the other four. [Fig.4] A kunta is tent-shaped. Hung over the bed it gave warmth and shelter during the cold season. Made of 95-100% wool the whole blanket is brittle and much rougher to touch than a kerka. A complete kerka should have six strips (22 cm wide), the sixth or lowest one being simpler woven than the other five. [Fig.5] In some areas there is a seventh strip in black and white called sigaretti to hang the kerka as a curtain in front of the bed. Well over 50% of a kerka (including the warp) is made with cotton yarn.

However, their ‘look’ has striking similarities. For instance, all the motifs and weaving techniques are the same, and on both types of arkilla we have a comparable rhythm of successive plain weave (cannyudi), weft float patterns (cubbe) and patterns in tapestry weave (tunne). While a kerka has just three dominant weft patterns with white tapestry on red grounds – the largest one being in the centre of the blanket - a kunta has four of them. And as a kerka of the first quality has twice six rather narrow weft float patterns, a kunta has five of them, the largest one being in the centre of the blanket.

On both, kunta and kerka, there are two major motifs as eye catchers in tapestry weave: the lewruwal (moon) and the gite ngaari (eyes of the bull), as the Peul say.

And for those readers who have followed us so far: a kerka has the lewruwal motif (moon) in the geometric centre - whereas a kunta has its lewruwal to the left and right of the centre – the centre itself being decorated by a huge diamond shaped pattern in weft float.

The moon motif lewruwal may be called differently in some regions – namely tiide eda: the forehead of the wild buffalo.

When we were in Wogo country in 1974 (Renée Boser-Sarivaxévanis and myself), we acquired three kunta for the Museum der Kulturen Basel. At that time the owners of the blankets or the villagers around there did not know the names of the patterns anymore. Names given to us were untranslatable for the linguists that we consulted in Niamey. Jean-Pierre Olivier de Sardan, the only anthropologist who describes an arkilla kunta, states that most names of the patterns are unknown to the weavers and to the old people in general or of unknown origin altogether (1969:108-109). As we did not stay long, our field data are poor.

When in Mali later, between 1978 and 1982, I put together some important documentation on the arkilla kerka - blankets that were still in use then. So all the terminology given here is in Fulfulde (the language of the Peul).

It is one thing to know the names of the patterns and it is another one to know how they are made. It is easier to understand these huge marriage blankets arkilla when looking at them through the eyes of a weaver – technically.

Looking back again at the first three photos above, Fig.1 shows the motif lewruwal (moon) with two stars kode to the left and right. Usually, there are four, six or eight stars. ‘Moon’ and ‘star’ are tunne, woven in the technique of tapestry. The two diamond shaped motifs above and below the lewruwal are called jowal meaning ‘rhomb’. As the two jowal are woven in a special kind of a weft float (in French “broché”) and not in tapestry they have another technical name, namely cukke. So, besides plain weave (cannyudi) we have three tunne (1 moon and 2 stars in tapestry) and two cukke. That is how the weaver thinks. After all, for him the weaving of an arkilla is a mnemotechnical challenge. “What I weave”, a weaver would say, “I have found with my fathers.”

That means, he repeats what he has learned. He doesn’t care whether a pattern is called ‘ears of the second wife’, ‘teeth of an old woman’ (black-white-black in reference to gaps between the teeth), ‘hoofs of a gazelle’, ‘upturned calabash’ or ‘tracks of a rabbit in the sand’. He is the artisan who masters the techniques and he rather thinks in terms of quality of the yarn, the colours, or his deal with the bride’s father and the bride’s mother who cooks his meals.

He will equally think about his salary: the more tunne he weaves and the finer and more eye catching they are the more additional income (cattle, millet, cash, kola nuts – a mix of all of them) he generates.

Arkilla kunta weavers were real master weavers. It would be wrong to think that their weaving was just repetitive. Now, in writing this contribution, I went through all the data I have on kunta blankets – 16 altogether – discovering, that no two kunta are exactly alike. There is a great range in designing the over all aspect of the blanket just in varying distances between patterns, the size of motifs and the combination of cukke, cubbe and tunne.

Fig.2 in fact is another jowal (rhomb), however of another kind than the two small jowal on fig.1. The weaver will call it cubbe, as the pattern is woven in weft float (in French “lancé”). This very cubbe here was probably in the middle of a kunta although, as it is rather small I am not quite sure.

The twisted fringes in yellow and red are a decoration. However, they serve as an important help to knot the newly woven strips together so that at last – after four or more weeks of weaving – the whole surface or the kunta can be admired before the sewing together of the strips starts. The very same fringes are on the kerka-blankets, too.

Fig.3 is another tunne extremely finely woven. It is called fedde (fed = finger), as all the weft threads forming the tapestry pattern have to be pushed through the warp threads with the fingers during the weaving process. On most kunta-blankets there are four weft stripes with the fedde-motif embracing several kode (stars) and a cubbe (woven in weft float pattern).

Throughout the old world – Middle East, North Africa, Europe – tapestry weaving was done by women on an upright loom. Not so in Mali: the Fulani of the Upper Delta of the Niger are an exception to the rule. Tapestry weaving is done on their horizontal treadle loom with one pair of heddles, and the weavers are men. That makes tapestry weaving interesting. It even seems that tapestry is a cultural marker, that wherever we find tapestry on West African textiles, there are Peul/Fulani around or the weaver has learned his profession with a maabo-weaver (singular of maabuube).

So, let us have a second look at that lewrual-moon-fig.1: it is a rather rectangular moon. In this case, all together, there are seven concentric layers or colours: light indigo blue, white, red, yellow, light indigo blue again, red, and white/blue. We can compare this kunta lewruwal with a kerka lewruwal (fig.6) having equally seven layers. This is just one way of talking about quality. The more layers, the more work involved, the better quality it is.

The striking difference, however, are the ‘antennas’ sticking out at the kunta lewruwal-fig.1. repeated below On kerka-blankets there are never such antennas. On arkilla kunta sometimes … or even often - but it depends where. These ‘antennas’ might exactly be one of these details a master weaver plays with and which might be in relation with the arranged ‘salary’.

On fig.1 we have 11 ‘antennas’ – quite a lot. Of the three kunta in Basel only one has such antennas, namely 10, on red ground. The other two have such ‘antennas’ on the smaller lewruwal which are towards both ends of the blanket on yellow ground, having 5 or 7 ‘antennas’ only.

That logic seems to be systematic: Either a kunta has its ‘antennas’ on red ground or they are on yellow ground. Not both together. Or there are no ‘antennas’ at all. And as the lewruwal on red ground is more to the centre of the blanket it is bigger and more important. Of the 14 kunta in my file where such details are visible only 3 have ‘antennas’ on red ground.

Maybe this is just a European approach: counting and quantifying for lack of other data. However, including other factors I have the feeling that the lewruwal motif on red ground with ‘antennas’ means ‘old’ … whatever that means. I know photos taken in Ghana in 2013 showing kaasa-blankets (the ordinary 6 striped woollen blankets of the Peul in Mali) in a ritual. As the patterns of the kaasa-blankets have changed considerably during the 20th century, it can be said that this very kaasa was woven well before 1930. That means the woollen blanket was kept in the tropics safely for over 80 years. The same is very possible for this piece of arkilla kunta-weaving.

Only one arkilla kunta-blanket is dated and has full information: the one at the National Museum of Mali, Bamako (inv.no. 2002.13.1) woven 1968. It is maybe the last one ever made.

So far, I have found no arkilla blanket in a museum collection dated before 1900. We have, however, one archaeological cotton cloth from the Dogon, dated to the 17th/18th century containing over 20 patterns strangely resembling the lewruwal motif of an arkilla kunta (fig.8 above - National Museum of Mali, Bamako 92-05-390 = H 71-2). Isn’t this an amazing cloth! It was found in a cave where all the human remains were female. So this is a female cotton shawl or wrapper. Originally, it had at least five strips.

Among the important corpus of published Tellem textiles (500 pieces, see Rita Bolland 1991) dating from the 11th to the 15th century, patterns with supplementary weft threads (“lancé” in French, cubbe in Fulfulde) go back to the 11th century. In rare cases there are even tapestry patterns in wool. Are all of them imported textiles from North Africa? Probably yes – although there might be just one exception (C 19-1, see Bolland 1993: 174, fig.32). In any case, fig.8 is the oldest tapestry pattern known for sure and woven on a West African treadle loom with one pair of heddles.

We have come a long way from arkilla kunta and Wogo to arkilla kerka and Peul to tapestry weaving in cotton found in a cave in Dogon country and going back 200 to 300 years. In order to end this story, I would like to invite the reader to come with me to Ghana. There, the most sacred and the most venerated cloths are called nsaa. Sacred drums or horns with human jaws sewn on them may be wrapped in nsaa. Dead people before burying are put on their bed, the room being decorated with nsaa. The first textile layer in a palanquin in which Akan chiefs are carried around is often nsaa. Although several authors had mentioned the importance of these nsaa- (or nsa-) blankets (Rattray, Ross, others) no researcher really followed up that topic. Except, maybe textile researcher Brigitte Menzel. “They are not only attributed protective but also healing properties”, she writes, and she carries on, “my aged Asante informants were unanimous of the opinion that this woollen textile, which they all called nsaa, is the highest ranking of all traditional textiles…“ And “in the olden days“ – 40 head loads each containing 2000 cola nuts or five healthy male slaves were paid up north in Salaga or Dagomba for such a nsaa. Although the word nsaa embraces all kind of woollen blankets from Mali Menzel stresses that nsaa means mainly: arkilla kunta … made 1000 km to the north, south of Gao (Menzel 1990:83).

We all know that the Golden Stool is the symbol and “national soul” of the Asante, as Rattray puts it. When the Golden Stool “was borne”, he tells us, it was “sheltered from the sun by the great umbrella, made of material called in Ashanti nsa (camel’s hair and wool). This umbrella was known throughout Ashanti as Katamanso (the covering of the nation).” (Rattray 1927:130) [Please note: “camel’s hair” is wrong. It is always sheep wool however of mediocre quality. But sheep it is.]

Click on the photos to enlarge.

Captions

Fig.1 see text

Fig.2 see text

Fig.3 see text

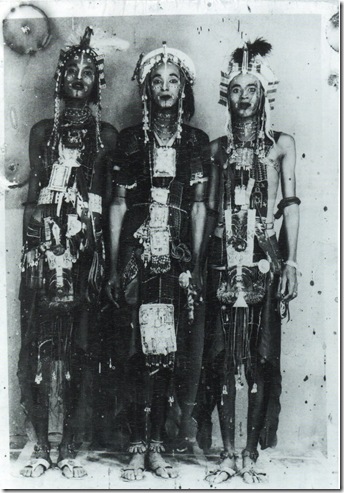

Fig.4 Arkilla kunta-blankets in the exhibition of the National Museum of Niger, Niamey in the late 1960s. One kunta is hanging over the bed, two others are spread on the bed and on the floor (Photo by Pablo Toucet, Photocard, coll. B.G.)

Fig.5 Arkilla kerka hanging in front of the bed. The centre of the blanket with the lewruwal motif is to the right. The white tapestry patterns on red ground to the left are called gite ngaari: ‘eyes of the bull’ (N’Gouma 1982, photo B.G.).

Fig.6 Central motif lewruwal (moon) of an arkilla kerka, Mali (1980, photo B.G.)

Fig.7 A = fig.1 Duncan Clarke’s lewruwal on red ground

Fig.7 B Lewruwal on red ground with 10 ‘antennas’, 4 stars. Museum der Kulturen Basel: III 20456

Fig.7 C Lewruwal on red ground with 11 ‘antennas’, 4 stars. National Museum of Niger, Niamey.

Fig.7 D Museum der Kulturen Basel: III 20462 – lewruwal on red ground without ‘antennas’. Eight stars. Below: lewruwal on yellow ground with 6 ‘antennas’.

Fig.7 E Museum der Kulturen Basel: III 20455 – lewruwal with 7 ‘antennas’ on yellow ground.

Fig.8 Single motif in tapestry on an archaeological cloth, Dogon 17./18.Jh. (National Museum of Mali, Bamako : MNM 92-05-390=H 71-2-II)

Fig.9 kunta in Ghana: nsaa (Photo: Werner Forman 1964, published by Duncan Clarke. 1997: The Art of African Textiles, p. 68, 69)

Fig.10 A maabo weaver at work. To weave a weft pattern with supplementary weft (cubbe) he uses a wooden board to count the warp threads. Below to the right we see two stars tunne on white ground (N’Gouma, 1982, photo B.G.).

Quoted literature

Bolland, Rita. 1991. Tellem Textiles. Archaeological Finds from Burial Caves in Mali’s Bandiagara Cliff. Royal Tropical Institute, Amsterdam; Rijksmuseum voor Volkenkunde; Leiden; Institut des Sciences Humaines, Bamako; Musée National du Mali, Bamako. With contributions by Rogier M.A. Bedaux and Renée Boser-Sarivaxévanis

Menzel, Brigitte. 1990. Textiles in Trade in West Africa. Presented at the Textile Society of America, Biennial Symposium. September 14-16, 1990. Washington, D.C. Proceedings of the Textile Society of America, pp. 83-93

Olivier de Sardan, Jean-Pierre. 1969. Système des relations économiques et sociales chez les Wogo (Niger).Université de Paris. Mémoires de l’Institut d’Ethnologie III. Institut d’Ethnologie Musée de l’Homme.

Rattray, Capt. R. S. 1927: Religion and Art in Ashanti. Oxford, The Clarendon Press.

Ross, Doran H. 1998. Wrapped in Pride. Ghanian Kente and African American Identity. UCLA Fowler Museum of Cultural History.

Click on the photos to enlarge.

![313285_190400007701425_925494034_n[3] 313285_190400007701425_925494034_n[3]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEjokADdvU7Xv8prwtaPJC6F9bMzU3xI16Ug-YZzPet2GE4mLyK6UCJd9sUCybg31z7hPW1L-LHHtyWVQip86R8hnm0SShwJuH3rJM_SCaXbnXwH3nLajxgDNtHci4WQT7edUn0Y0SDyZnCl/?imgmax=800)