While run of the mill Asante kente cloths woven from rayon thread and mostly dating from the 1970s and after are easy to find, top quality silk cloths woven in the early part of the twentieth century are extremely rare and becoming increasingly difficult to source. The images below show a glimpse of some or our current inventory. Full views and more details on our site at adireafricantextiles.com

Friday, 2 October 2015

Tuesday, 8 September 2015

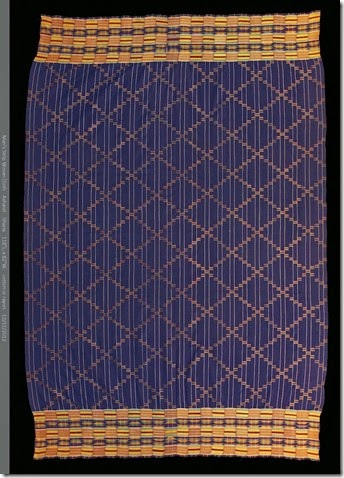

Cloth of the month: A fine blue and white Asante kente.

K260 - Exceptional Asante mixed strip blue and white cotton kente cloth. Composed of four repeats of six different strip patterns, this cloth is notable both for the fine quality of the weaving and for the addition of borders (a feature not usually found on Asante blue and white cloths of this type.) The interaction between the blue extra weft float motifs that make up the border and the different blue and white patterns beneath makes a subtle and interesting visual impact. In excellent complete condition. Dates from early to mid C20th. Measurement: 127 ins x 75, 323 cm x 190.

Click on the photos to enlarge. See this cloth on our New Acquisitions Gallery or visit our Asante Kente Gallery.

Saturday, 21 March 2015

Nkontompo Ntama–The Liar’s Cloth

I first met Claude Delmas a couple of years ago when I gave a talk on African textiles at the Oriental Rug Society here in London and she had brought along several of the cloths she had woven. These turned out to be remarkable reproductions of some of the more unusual West African textile designs, including the intriguing Asante kente pattern known as “liar’s cloth.” The article we reproduce here with Claude’s kind permission was first published in 2008 in the Journal for Weavers Spinners and Dyers #227 . Having seen a loom set to weave “liar’s cloth” in the collection of the Deutsche Textilmuseum, Krefeld, I can confirm that Claude’s solution to the mystery of this design is the correct one.

“Nkontompo ntama – The Liar’s Cloth

Claude Delmas, London Guild

Looking at John Gillow’s book African Textiles my eye fell on the image of a lovely blue and white strip woven cloth from Ghana decorated with very precise inlay motifs. The caption read: ‘Liar’s Cloth in which blue warp threads are taken down the length of the cloth in stepped fashion’. The picture was so small that I needed a magnifying glass to see the blue stripes at all. There were three of them on one side of the strip which seemed to turn at right angles into the weft at regular intervals to continue on the opposite side. How could that be done?

The Research

Picton and Mack in African Textiles refer and defer to Venice Lamb’s exceptional field work in West African Weaving, and show in black and white a Liar’s Cloth from her collection – frustratingly indistinct for the non-expert. In her own book Lamb illustrates ‘an old Asante cloth with an inverted “liar” pattern. The liar pattern is fascinating: the warp thread is carried from side to side.’ In the small catalogue of the exhibition at the Halifax Museum of The Lamb Collection of West African Narrow Strip Weaving in 1973, there is yet another Liar’s in black and white. Hardly enough visual information to attempt such a feat on the loom! Nor were descriptions precise enough to help: Venice Lamb writes: ‘…there are a few devices which are rather harder to classify, such as the ‘floating warp’ technique used by Ashanti weavers to produce what they know as ‘liar’s cloth’, a kind of Greek fret pattern executed by shifting a warp stripe from one edge of the web to the other at regular intervals.’ And Kate Kent: ‘Ashanti weavers formerly produced…a handsome fabric called “liar's cloth” (Nkontompo ntoma), in which narrow lines meandered the length of a plain weave strip – either white lines on an indigo blue ground, or blue on a white ground. Blocks of weft-patterned design were woven over this warp pattern at regular intervals.’

It was the ethnographer R.S.Rattray in 1927 who established the name of the cloth as Liar’s. He made an extensive study of West African strip weaves, and put together a large collection of swatches, now in the British Museum, of both silk and cotton fabrics. Rattray’s swatch number 95 is a blue silk with two yellow and 2 red warp stripes and swatch 106 shows their meander into the weft and back on the opposite side. He elucidated the names given to the cloths according to the order and colour of warp stripes and attempting a description of the symbolism behind those names. His entry reads, ‘Nkontompo ntama’ (the liar’s cloth). The King of Ashanti is said to have worn this pattern when holding court, to confute persons of doubtful veracity who came before him.’ In 1969, another researcher Kate P. Kent was told that the shifting blue lines represented the liar’s speech.

Intriguing as it is, the name ‘liar’s’ and its meaning has survived, and it was interesting to find on the internet a mention of a Yale University thesis quite unrelated to textiles entitled ‘The Liar’s Cloth: Producing Veracity in the Victorian Courtroom’. Ethnographers seem to have been more exercised by the symbolism of the names than by the technique, and by their historical relation to status in the rigid hierarchy of the old Ashanti empire, where some combinations of stripes and patterns were reserved for royalty and nobility, the main sponsors of the weavers.

Traditional Kente cloth

Nowadays, after an eclipse lamented by writers of the 70s and 80s, it seems that narrow strip weaving is alive and well, whether worn as a mark of African identity or purchased by tourists, and the professional weavers formally trained by ‘masters’ in their workshops now even include women – witness a video recording produced in 1998 by the Open University as material for its Art and its

Histories course. The narrow strip loom of Ghana is well documented. The bundle of its 25 metres long warp is tensioned on a drag weight, its double heddle and reed, suspended from a frame, both pairs of heddles worked by the weaver’s feet. One heddle, the asatia, is threaded for the warp-faced tabby weave, the other, the asanan, threaded six by six ends, making itpossible to weave a weft-faced fabric at will and partially or completely cover the strip with decorative inlay left to the creativity of the weaver. Although some liar’s lines are worked along strips completely clear of inlay, the cloth that intrigued me had many indigo motifs and presented me with a double learning challenge. In The Art of the Loom Ann Hecht has a diagram showing the way to thread a modern four shaft loom to work like the double heddle loom – ground weave on shafts one and two, and weft-face on three and four, giving the same flexibility.

It seemed to me that in order to meander from side to side, the blue warps needed to be weighted independently at the back of the warp beam. To interlace with the weft, they had to be caught in heddles and go through the reed. My Texsolv heddle’s eye was large enough to take a small flat stick (a drinks stirrer) with the warp end wrapped on it, which I could manipulate in and out, use as a shuttle to weave in as weft, and return as warp, through empty heddles reserved on the opposite side, then back to their weight at the back of the loom. Not easy, but possible. Yet decidedly not the Ashanti way! More research was needed.

Floating warps?

Venice Lamb mentions a ‘floating warp’ technique in connection with the liar’s cloth. A few pairs of supplementary warps anchored independently on the cloth beam and weighted at the back would lie idle in the shed, neither held in the heddles or the reed, until lifted by the shuttle to appear as intermittent decoration on the cloth. As the liar’s lines weave continuously, it seemed to me that heddles were indispensable and floating warp not the solution. Another description suggested that ‘To make the meander pattern supplementary warps of liar's cloth served at times as weft. These were probably passed between the dents of the beater and through the eyes of the plain weave heddles when the loom was strung. They were thus part of regular plain weave when in the position of warps. When a warp pair was to be turned and used as a weft, it was cut to the appropriate length and woven in. The cut end would then fall free of the beater, but remain in the heddle eye. When it was to be re-utilized as warp again, it was pinned to the surface of the cloth – then woven in. (Ashanti weavers are accustomed to pinning any broken warp back into position in this fashion. The process outlined above was suggested by a young Ashanti weaver)’.

Convincing as this was, it failed to work for me, because I still had to move the blue warps from one side to the other, and I was left at each turn with four cut ends to darn back into the cloth in the usual way.

A theoretical solution

Not until I discovered the extraordinary survey and descriptive catalogue by Brigitte Menzel, mentioned in other works but never actually quoted or translated, Textilien Aus Westafrika, did I begin to see the light. Her swatches, like Rattray’s, relate mainly to the arrangement of warp stripes, but unlike him she concentrates, instead of the naming of cloths, on the exact thread count for each colour stripe. The swatch for ncontompo ntama shows 3 pairs of warps on the left, and the description says they are turned into the weft at 20cm intervals then vertically back into the warp. But it was the drawing that explained all. The warps are weighted, but at the front of the heddles! The blue threads are therefore wound on to the warp beam with the rest. And it dawned on me that there has to be two sets, one at each side of the strip. One set only weaves at a time, while the other rests attached to the weight, threaded in the heddles, but free of the reed. After 20cm of plain weave, one pair after another is cut off, freed of the reed and woven as weft to the appropriate point on the web to meet its opposite partner, which is detached from the weight, pinned on the cloth to be woven in on that side for the next 20 cm.

Looking at the real textile

I was fortunate enough to be able to test this theory on a genuine liar’s cloth thanks to John Gillow and the generosity of his friend Molly Hogg, who owns an old and damaged but very beautiful one. Like all Ashanti cloths, its web is very dense warp faced, about 80 epi (a lot more than I had guessed) of fine machine spun cotton. The blue pairs are equally fine, and only show faintly on the cloth. The strips have been sewn together with exquisitely small stitches and the arrangement of the strips aligning the liar’s lines back to back – so to speak – create a fretwork into which the indigo motifs are slotted. It is impossible to know whether it ever had a traditional heading of densely brocaded designs at each end as it is coarsely hemmed instead. Nor can one tell if it ever had more than the present 21 strips. Very few of the inlay motifs repeat many times, some only occur once, and this somehow reveals the skill of its imaginative weaver.

With a magnifying glass, it is possible to ascertain that the threads are cut at the turn from weft to warp. Sometimes there is a small but discernible gap, and one can detect the closely cut thread ends. They are held by the density of the web, in the same way as the brocading wefts, without knots or darning in. Perhaps these cuts are the lie, the deception; The line doesn’t ‘turn back into the warp’, it is not continuous. Instead it is replaced by a partner.

Detail of Claude’s completed liar’s cloth.

The practical solution

To put this new understanding into practice, I warped up a long 4 inches wide strip with very fine white silk at 72 epi and dyed some silk in indigo for the supplementary weft. I included three pairs of indigo warp stripes on each side of the strip, entering them all in the heddles normally. However only one set of blue stripes went through the reed, while the other was weighted down in front of the heddles. After 20cm I needed to go through the following steps to turn the liar’s lines:

1. wind on the weaving so there will be enough space in front of the heddles to manipulate the blue threads.

2. disengage the first blue pair from the weight, bring it up through the reed at the appropriate place and pin it on the woven cloth.

3. cut the opposite blue pair long enough to become weft . Disengage the cut end from the reed and weight it in front of the heddles with a second weight.

4. weave the two cut warps into the weft one after the other to meet the pinned threads Then weave with the ground weft until the next blue pair needs turning into weft and repeat steps 2 – 4.

Two weights are needed until all three pairs have changed sides. After weaving half an inch or an inch, remove all three pins and cut all loose threads lying on the surface of the weaving closely. Because the sett of the cloth is very high, the cut ends stay caught in the web. For the next 20cm one can concentrate on working the inlays patterns, before returning the liar’s lines to the opposite side once again.

It seems easy, so it is likely to be right. Another interpretation of the name Liar’s cloth is that anyone who says they can weave it is a liar: I am hoping I have disproved that saying.

Friday, 26 September 2014

Two Asante Silk Kente Explored

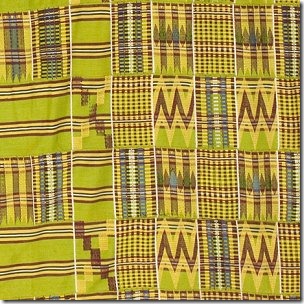

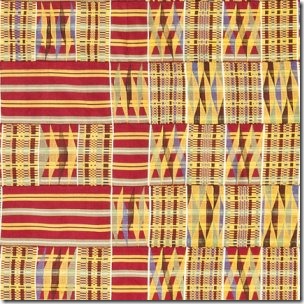

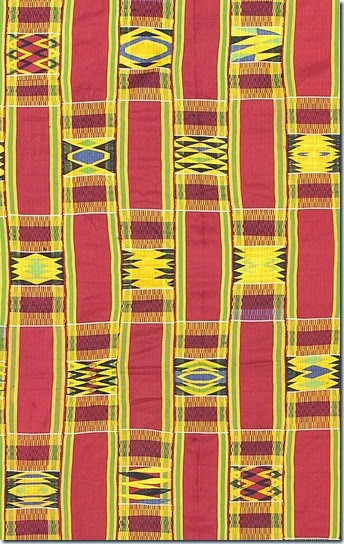

In today’s post I will be taking a look at two extraordinary Asante silk kente men’s cloths and airing some preliminary thoughts and queries that they suggest in relation to creativity and innovation. The first, above, a predominantly green version of the classic “a thousand shields” design, is from the William Itter Collection in the USA . The second, below, that we found recently and is now in a UK private collection, is a warp stripe patterned cloth called “Ammere Oyokoman” in the familiar red green and gold colours so favoured by Asante weavers. Both cloths are woven from silk and both can be assumed to date to the first third of the C20th.

Looking first at the green cloth, on first glance it appears to be a standard version of a familiar design, such as the cloth, also from the William Itter Collection, below.

The diagonal grid pattern in the main field of the cloth is made up of small rectangles, recalling the rectangular shape of the wood and leather shield once used by Asante warriors and giving the cloth its name Akyempem, or “a thousand shields.” Incidentally the vast majority of Asante kente cloths were named after the warp stripe pattern, this is an exception. However the technique used is quite different as detail photos show:

Compare the usual version, above, where a supplementary weft float in red and yellow on a blue and white warp striped, warp faced background, is used to create each rectangle in the grid of “shields”, with the one below:

Here the entire cloth is weft faced and the grid of red and yellow shields is created as weft faced rectangles using a tapestry weave technique. I can’t recall another example of a fully weft faced Asante kente and I have certainly never seen tapestry weave used in this way. Also very unusual is the background colour that alternates picks of yellow green and blue that blend to a muted green overall effect. These threads are not plied together to create a “tweed” in the way that Ewe weavers sometimes do. We should also note that using this technique to reproduce the design would have been both significantly slower (as more weft threads and hence more weft picks are required) and, because it needed far more thread, considerably more expensive that the standard method.

Turning to the red Oyokoman cloth, here the notable feature is a large array of unique weft float patterns.

The grid framework imposed by the interaction of warp and weft threads naturally leads itself to the creation of diamonds, triangles, and regular stepped patterns and Asante kente weaving exploits these shapes to the full. Here though the master weaver has transcended the limitations of the form by weaving ellipses and even circles, as well as fragmenting the standard diamond shapes to create more complex composite motifs.

While my primary purpose here is simply to register, share, and admire these two wonderful cloths, to me they also raise a number of interesting questions about innovation and creativity in kente weaving and perhaps pose a challenge to any over simplistic contrast between creative expectations expressed in Asante as opposed to Ewe textiles. Anyone familiar with the two genres is aware that there is a greater variety of styles and techniques apparent in “Ewe kente” than in Asante. As William Itter noted in our discussion of these two cloths “regarding the controlled or restrained composure of construction and design found in Asante cloth from the more expected/unexpected variety of design in Ewe wraps.”

Here we have seen two superb examples of novel and innovative extension of established techniques that nevertheless remain within the expected parameters of Asante kente design in terms of cloth layout, overall patterning etcetera. Such cloths, I would suggest, arise out of a sustained interaction between an experienced master weaver and a exceptionally well informed and perceptive patron, in this context we might suppose an Asante king or senior chief with a deep knowledge and understanding of the existing pattern repertoire who is able to finance and encourage such sophisticated results over a considerable period. This hypothesis would fit with what little we know from the unfortunately rather inadequate ethnographic documentation of Asante kente production for royal patronage in weaving villages such as Bonwire. It would however, in my view, be over simplistic to contrast this with a more open pattern of patronage for Ewe cloths as alone explaining their greater variety. I will return to this complex topic in future posts.

I am very grateful to William Itter for generously sharing his photographs. My thanks also to the owner of the Oyokoman cloth. Click on the images to enlarge.

Wednesday, 23 April 2014

New light on an Ewe chief

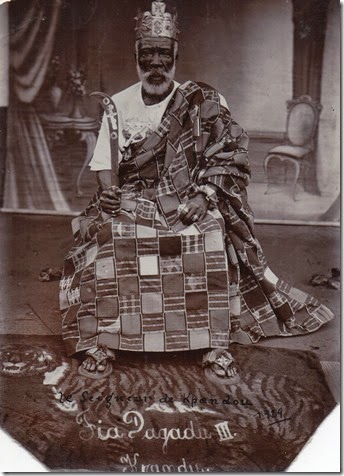

In her pioneering book West African Weaving (Duckworth Press, 1975) Venice Lamb published the photograph above (source: Wilmarth family private collection) depicting an Ewe chief with his court retainers. She suggested that it showed an Adangbe chief and goes on to describe the features of the cloth that he is wearing as distinctive of what she calls “an earlier type of Adangbe design” , although it is unclear if she has any source for the geographic identification or is basing it only on what she perceived to be the origin of the cloth. She also regarded the picture as dating from the nineteenth century. This photograph is interesting as there are relatively few early photographs of Ewe chiefs, perhaps because they lacked the elaborate large scale ceremonials and court paraphernalia of the Asante as well as being of lesser political significance in the Gold Coast colony.

For some years I have had a postcard that clearly shows the same man, wearing the same cloth (and the same rather odd crown.) With the photographer identified as “Cliché G.O.” the card is captioned “Palimé (Togo) – Le Chef du village de Kpandu”. Palimé (Kpalimé) is a town in Togo quite close to the Ghana border, while Kpandu is on the Ghana side on, now on the shore of Lake Volta. Both fall within the more northern cluster of Ewe weaving groups near the town of Hohoe (that Lamb rather confusingly identifies as the Central Ewe) rather than the more southerly Adangbe or the coastal Anlo. Whilst there is no guarantee that the caption information is correct (misleading captions on postcards from this period are quite widespread) we can at least note that before the 1914-18 war Togo was a German colony and postcards before that date are captioned in German rather than French.

Malika Kraamer, in her unpublished Phd thesis on Ewe weaving (Colourful changes: two hundred years of design and social history in the hand-woven textiles of the Ewe speaking regions of Ghana and Togo (1800-2000), SOAS, 2005 –now online here) discusses the corpus of early photographs showing Ewe textiles (most drawn from the archives of the Basel and Bremen missions and mainly online here). Among the images that she found with the Bremen Mission is a third photograph of the same chief, again in the same attire. She notes that the same unidentified chief was shown by Lamb and perhaps influenced by her suggests it is a late C19th or early C20th image (at that point it seems she did not have access to the postcard view.)

A couple of weeks ago I was able to buy a group of three photographs from a French source whose grandfather was a trader in Togo in the early part of the twentieth century. One of these photographs, shown below, is a print of the same image as that in the Bremen archive.

Our chief wears his now familiar cloth and crown, but unlike the Bremen copy this print has two captions and, on the reverse, the photographer’s stamp. The first caption, apparently contemporaneous with the print, reads “Fia Dagadu III, Kpandu”, while the second, written in ink, reads “le seigneur de Kpandou, 1929.” On the reverse is the photographer’s stamp “Louis A. Mensah, Photographer.”

In addition to finally identifying this distinguished looking chief, for me these images raise a number of interesting questions about Ewe textile production and use. Why is the same cloth worn in all three photographs ? Is it the only one that he had or his favourite among several ? Might there be other, earlier or later, photographs of him wearing a different cloth ?

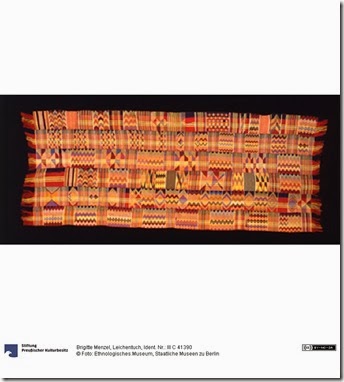

What can we say about the cloth itself ? Malika Kraamer identifies the style as atisue based on the short weft faced block structure. As she discussed, both the naming and the design evolution of Ewe textiles were extremely fluid and complex. This type of cloth, in which almost square weft-faced blocks alternate with similarly sized warp-faced sections decorated with supplementary weft float motifs, was certainly among the more elaborate and highly prized types woven in the first half of the twentieth century. A fine example that is on our gallery at the moment is shown below.

Is Venice Lamb correct in attributing this style of cloth primarily to the Adangbe weavers (Kraamer calls the same group Agotime after the main weaving village in the area) ? I would suggest that at present the necessary field research that might perhaps allow us to clearly attribute many of the huge variety of Ewe cloths to specific locales has yet to be carried out, although based on Kraamer’s work some preliminary suggestions for some styles might be possible How did geographical variation interact with individual innovation, workshop styles etcetera ? We simply don’t know. We do know however that cloths are highly mobile artefacts, with prized pieces being traded over a wide area. Did master weavers whose work was in demand also move to supply wealthy patrons ?

And what about the odd crown ? Both colonial authorities and European traders imported items of royal regalia and prestige goods that they gave or sold to local rulers they wished to influence. The tiger patterned rug in the third photograph clearly falls into this group and I would suggest the crown does also.

Click on the photos to enlarge. Click here to view our current selection of Ewe textiles.

Tuesday, 1 April 2014

“African Rulers Here”

Press photo titled “African Rulers Here” 27.9. 1948

Caption: “A party of African rulers, here for the African Conference opening on Wednesday at Lancaster house, arrived at Euston this evening. (L- R) Essuma Jahene and Sir Tsibu Daku.”

Thursday, 31 October 2013

Asante Kente Cloths in the Ethnological Museum, Berlin

A small selection from the large number of Asante kente cloths collected by the late Dr Brigitte Menzel are now online on the website of the Ethnological Museum, Berlin. Menzel’s field research on Asante weaving in the 1960s, sadly largely unpublished, remains the only in depth investigation of the tradition, and she was able to collect a group of cloths of unrivalled quality. Most of these are in the Berlin Museum where she worked for many years (others are in the Textilmuseum, Krefeld, and the Rijksmuseum Volkenkunde, Leiden.) Small black and white images of these cloths and many others are published in Menzel’s three volume catalogue Textilien aus WestAfrika (Berlin 1972).

Click on the images to enlarge. You can see these together with other early and important Asante kente on our Pinterest page here, and view the Asante kente we have for sale here.

Saturday, 25 May 2013

Thursday, 23 May 2013

Cloth of the month: “Mmaban”–a mixed strip silk Asante kente.

K224 - A superb silk man's kente with six different warp striped patterns and a fine variety of supplementery weft float designs. Cloths with mixed pattern strips were called "Mmaban", meaning mixed, but each warp stripe pattern had it's own name.

The second and sixth strips appear to be variants of a design that Rattray (1927:241) calls "Asonawo mmada" - "The clan tartan of the Asona tribe; the father of King Bonsu Panyin was Owusu Ansa, who belonged to the Asona clan, the first of that clan ever to be the father of an Ashanti king. The pattern is said to have originated in this fact." The third strip is called "Oyoko ne Dako" - the Oyoko and Dako clans (Rattray 1927:239) after two rival clans in the royal matrilineage who fought a civil war in the early C18th. Strip four is unidentified. Strip five is called "Mamponhemaa" - Queen mother of Mampon (Ross 1998:113).

Although mixed strip rayon cloths are fairly common a silk example of this quality is extremely unusual and would most likely have been commissioned for a king or senior chief in the early decades of the C20th. Condition is excellent.

For size, price, etcetera please visit our gallery of Asante kente here. Click on the photos above to enlarge.

Wednesday, 3 April 2013

Cloth of the month–an exceptional Bondoukou man’s cloth.

fr473 - One of a very small number of museum quality Bondoukou men's cloths, this subtle and beautiful piece uses complex blocks of coloured weft threads muted by the predominant indigo warp as the sole decorative effect. Although this is a very old decorative technique found in some of the earliest Ghanaian textiles the sophisticated effect achieved here by varying the colours and the placement of blocks is to my knowledge unique. One strip is missing from each edge (they were likely removed because they were excessively frayed) but the cloth is otherwise in very good condition with no patches, holes, or stains. Dates from C19th or early C20th. Measurements: 118ins x 71ins, 300cm x 180cm. PRICE: Email for price.

Bondoukou is in the north east of Ivory Coast, not far from the border with Ghana. Culturally and historically it shares many features with the nearby Brong-Ahafo region of Ghana, such as small Akan kingdoms and chieftaincies ruling primarily farming peoples and significant communities of Muslim traders of Malian ancestry. The textiles of this region, as I discussed in my article in Hali magazine a few years ago, now on my website here, share features with both Asante and Ewe cloths from Ghana and with Ivoirian cloths of the Guro and Baule.

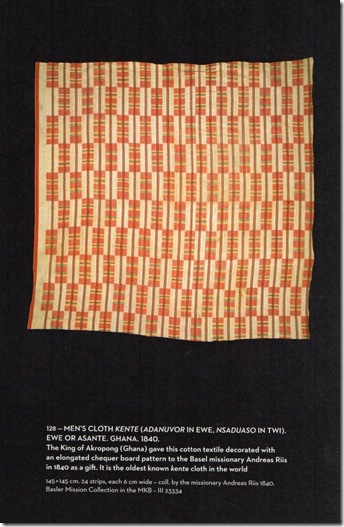

Two cloths from the collection of the Museum de Kulturen, Basel, published in the important exhibition catalogue Woven Beauty: The Art of West African Textiles edited by Berhard Gardi (Basel, 2009) illustrate the early use of the same technique.

This cloth, collected in 1840, is the oldest documented kente in the world. Here red, yellow, and blue weft stripes are muted by the white warp. The author notes that it may be attributed to either an Asante or an Ewe weaver – although I would suggest the red edge strip is strongly indicative of an Ewe origin.

This second piece, collected in 1886, is attributed by the author to the Asante on the rather weak grounds that the collection location is nearer Asante than it is to the Ewe. It is closer to our cloth in that indigo and white stripes are used in the warp although the variety of weft colours is still much less, and the pattern layout much less sophisticated. Click on the photos to enlarge. More Bondoukou cloths on our website here.

Thursday, 12 July 2012

A Weft Faced Ewe Kente

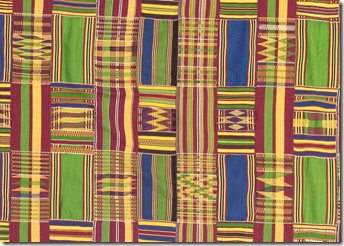

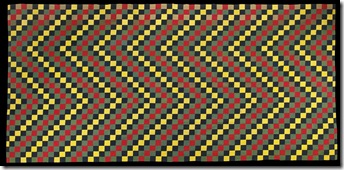

Continuing our exploration of some recent additions to our Ewe Kente gallery today’s post looks at a dramatic style of weft faced Ewe cloth in which solid blocks of colour are arranged in patterns across the fabric.

Ewe649 - Fine Ewe chief's cotton cloth in the weft faced, so-called "checkerboard" style, with subtle variation in the shades of green and pale greenish brown used with the bolder red, blue, and yellow blocks. It is rare to find cloths of this style that are, as this one is, complete and intact with no patches or repairs. Condition is excellent, age circa 1910-30s. Measurements: 130ins x 70, 330cm x 178.

Click on photos to enlarge…

The Ewe name for these heavyweight weft faced cloths is titriku which just means “thick cloth.” It is possible that they are primarily the work of weavers in the more northerly and easterly, and perhaps peripheral regions of what is now regarded as the Ewe regions of Ghana and Togo, although much further research is needed. The late C19th Basel Mission photograph below (reproduced in Lamb West African Weaving 1975), which shows the man at the left wearing a similar cloth, is one of several that confirm that this style was produced in area in the nineteenth century at least, if not earlier. The chief at the centre may be seen, wearing what appears to be the same cloth, in another image on our website here.

In photographs they can sometimes be confused with superficially similar block patterned cloths called tapi woven in Mali, a much more recent tradition that Bernhard Gardi sees as dating only from the 1950s. However the latter have different layouts, different colour combinations, and a different weight and texture.

For this and other fine Ewe cloths please visit our Gallery here.