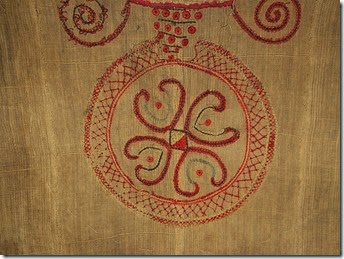

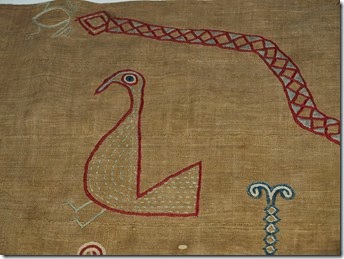

In my last post I looked at two rare embroidered robes from Liberia or Sierra Leone in the British Museum collection. Today I turn to a third robe, also from Sierra Leone, that is in an even more unusual style. The vast majority of robes from the region were tailored from either plain or simple warp stripe patterned cotton cloths in shades of white, brown and indigo. They can be distinguished from other West African robes by their distinctive front pockets and their overall design – according to Venice Lamb there were two styles: a simple sleeveless tunic called in Sierra Leone kusaibi, and a more complex sleeved robe called a duriki ba. A very few surviving examples (two of which we looked at) were embroidered and fall into a group that Bernhard Gardi in his important book Le Boubou – c’est chic calls Manding robes.

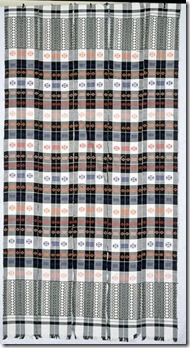

However there remains an even smaller number of robes from the same region tailored from the elaborately patterned kpoikpoi cloths for which Sierra Leone weavers were so notable. This robe, part of the British Museum’s Beving collection, was collected at least by 1913 and most probably dates from the second half of the nineteenth century. It was apparently (Lamb 1984:136) collected in Bonthe region, Sierra Leone. It is among less than ten robes I am aware of that have been made from kpoikpoi cloths.

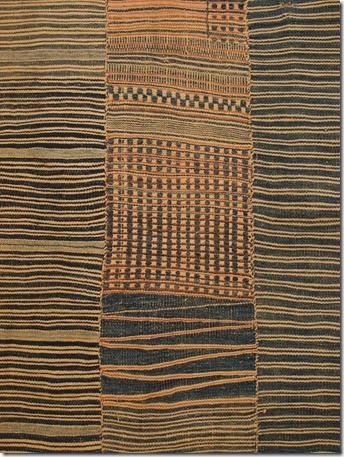

The structure is simple – an existing small cloth is simply folded in half width ways, a neck hole made, and a patch pocket added at the front. This results in a robe made up of seven strips of cloth, each around 18cm in width, and a total size of 124 cm width by 96cm length. The pocket is made from a square piece of cloth, one and a half strip widths in size, with the small corner fold typical of robes from the region. The lower half of each side is sewn up with the rest left open to create armholes. However in marked contrast to this simple tailoring the cloth used to create this robe is exceptionally elaborate. On the pocket detail above we can see blocks of thicker indigo dyed thread inserted as supplementary weft floats half way across the strip in sufficient quantities to distort the flow of the ground weft into a curved pattern. This is just one of the many variations used in a way that seems to me to suggest a deliberate echo of the embroidery patterns normally found on the pocket and chest areas of prestige robes. In particular when we look at the back of the robe we see that the small block of checkerboard pattern largely concealed by the pocket is repeated.

Elsewhere we see the use of tapestry weave techniques to create distinctive triangular patterns that are a feature of the more complex styles of Sierra Leone weaving.

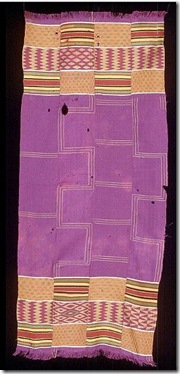

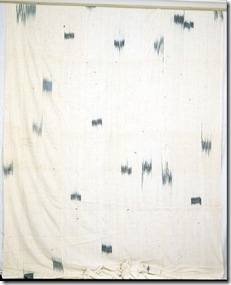

The detail above from the lower left of the back also shows some of the remarkable variation in weft stripe placement and simple variants of the weft float patterning the weaver has utilised. To me though the most interesting feature, and the strongest evidence that this cloth was woven to order with its use as a robe planned is the contrast in colour between the front and the back. On the front of the robe white is the dominant colour, but on the back there is a preponderance of light blue indigo dyed thread. The pattern diverges at the fold in the centre of the cloth, yet the strips used are continuous, strongly suggesting that it was woven with this use in mind. We can see this in the photograph below where the two sides are shown together (please excuse the inept photoshop.)

Can anything useful be said about the ethnic origin of this robe ? Venice Lamb published it (1984:137) with a caption ascribing it to the Vai ethnic group, but in the text is much less certain noting only “It is possible that this garment is an example of Vai inventiveness in weaving.” However I am not convinced that there is sufficient evidence to distinguish Vai weaving from that of the larger group of Mende weavers. Easmon (1924:22) noted that kpoikpoi cloths were “essentially a Mende cloth, and is also made by the Gallinas [Vai]”. Very few of the small number of early Sierra Leone cloths in museum collections have any detailed collection data and where they do it is not generally sufficient to confirm that the piece was woven in the same place as it was collected. Prestige cloths and prestige robes were important trade goods and may well have been traded a considerable distance from their place of origin. Bonthe, where this cloth was collected, was mainly inhabited by Sherbro people . We might also note that the whole process of assigning a particular cloth style to a particular ethnic group is extremely problematic.

All photographs above by Duncan Clarke. Click on the photos to enlarge.