A second Ifa divination cup with a representation of a treadle loom weaver. Present location unknown. Thanks to Bernhard Gardi for the photographs.

Friday, 20 June 2014

Tuesday, 17 June 2014

New Exhibition: “Couleurs de Vie” at Casa Africa/Espace Cosmopolis , Nantes.

“Exposition "Couleurs de vie, vie en couleurs"

Du 3 au 20 juillet

En Afrique, peut-être plus qu’ailleurs, les tissus racontent des histoires, petites et grandes. Celles des échanges Europe, Afrique, Asie, celles des femmes et des hommes qui les portent. Alors que pour un regard non initié, le wax est simplement un tissu aux couleurs chatoyantes, il est, pour l’œil averti, un "alphabet du corps" : par exemple, le pagne ''Ton pied mon pied'' revendique l’égalité entre l’homme et la femme ou celui représentant une main avec des pièces de monnaie illustre que l’union fait la force. Les tissus se font langage imaginaire, quotidien, commémoratif, sociétal, politique ou religieux. Expositions, films, défilés, ateliers proposés par la Casa Africa Nantes permettront de décrypter ces messages.”

“Expo Wax

Cette exposition présentée a pour but de montrer la richesse des textiles africains. Au sein des sociétés africaines modernes, le wax perpétue un ancrage identitaire traditionnel et il est aussi un support de communication. Les tissus racontent des histoires et nous les aborderons sous plusieurs axes : le langage imaginaire, quotidien, commémoratif, sociétal, politique ou religieux. Ils offriront au grand public des clés de compréhension des textiles imprimés en wax et aux populations issues du continent africain un espace de valorisation et d’expression de leurs cultures d'origine.”

+

“Wax Dolls: Omar Victor Diop” and more.

Full details here.

Friday, 13 June 2014

A Yoruba Ifa Diviner’s Bowl.

A few months ago I posted a photo of this unusual object I had noticed pictured in a dealer’s advertisement in an early issue of African Arts magazine. As I noted at the time depictions of any form of artistic activity are extremely rare in Yoruba ritual sculpture and I know of only one other depiction of a weaver – another Ifa diviner’s bowl, that one showing a woman weaving on a vertical loom, in the Ethnographic Museum in Berlin. I have now found the bowl listed in the collection of the University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology, online here, from which these three photographs are taken.

As these photos show it is a surprisingly accurate depiction of a Yoruba aso oke weaver at work. Note that it is miscataloged as a “kola nut presentation bowl” – actually it is in the standard form of bowl’s once used by Yoruba Ifa diviners, babalawo, as a prestige holder for the 16 sacred palm nuts that they used to cast divination signs.

Incidentally, the same museum has some very early and interesting West African textiles in it’s collection, many of which may now be viewed online. I will be discussing some of these in future posts.

Wednesday, 11 June 2014

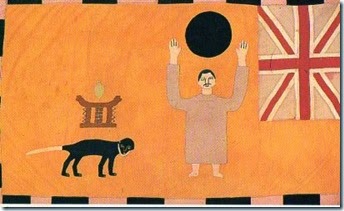

Cloth of the Month: A Fante Asafo Frankaa

Asafo112 - Exceptional and interesting mid C20th Fante Asafo flag (frankaa) illustrating the proverb "the spider (Ananse) was on the stool before God made the world." Condition: has a number of very small rust holes. Measurement: 53ins x 33 ins, 135cm x 84cm.

Ananse (Anansi) is a key god in the religious mythology of the Akan peoples of Ghana (including the Fante) and related diaspora groups. He is typically represented, as here, by a spider, the literal translation of the word ananse in the Akan language. Here he is associated with the wisdom and cunning of the gods and by virtue of the depiction seated on a chiefly stool, is claiming that wisdom for the chief. In Akan culture the stool is closely associated with the identity and persona of its owner during his life, and in many cases after the owners death his stool would be painted white and preserved as a focus of libations to the deceased ancestor in an ancestral “stool room.” It is also the key embodiment of royal and chiefly identity and of royal regalia.

The most interesting feature of this flag is the way in which a specifically local Akan set of iconographic features is combined with other imagery apparently of a more global origin. Below the spider on it’s throne we see a crawling monkey like figure.

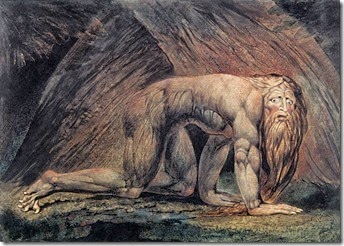

The function of this image in the interpretation of the flag remains obscure but in their caption to a very similar flag by the same artist, shown below, Adler and Barnard in their book Asafo ! African Flags of the Fante (Thames and Hudson, 1992, figure 42) suggest that the image is drawn from a popular print based on William Blake’s classic representation of King Nebuchadnezzar.

This is certainly an intriguing idea, and anyone who has listened to the radio in Ghana would not under estimate the extent of reference to even more obscure biblical figures, but I would be curious to see the source of this link in a popular print.

By the same token the depiction of the figure holding up the world may perhaps be drawn from a print depiction of Greek god Atlas.

What are we to make of the similarity between our flag and the one in the Adler collection, below ?

Each flag artist developed a personal style within the overall expectation set by the format. Several of these artists were identified and discussed in the earliest published research on the tradition by Doran Ross in his small book: Fighting with Art: Appliqued Flags of the Fante Asafo (UCLA, 1979) from which most subsequently published information has been drawn. Close attention to genuine flags allows one to identify individual styles and hands, and within that it was not unusual for an artist to repeat a design that either he or his patrons felt had been particularly successful and admired.

Click on the photos to enlarge. Click here to visit our updated gallery of Asafo flags for sale.

Tuesday, 3 June 2014

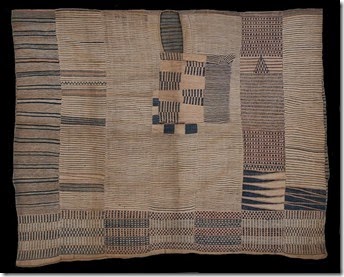

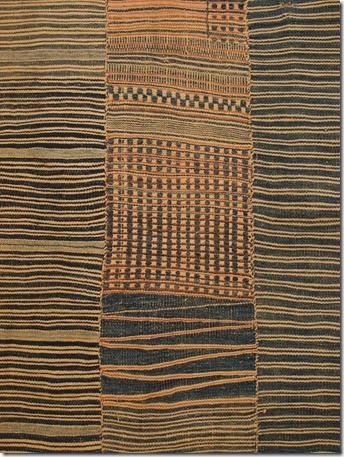

African Textiles in Close Up #2: a Sierra Leone robe.

In my last post I looked at two rare embroidered robes from Liberia or Sierra Leone in the British Museum collection. Today I turn to a third robe, also from Sierra Leone, that is in an even more unusual style. The vast majority of robes from the region were tailored from either plain or simple warp stripe patterned cotton cloths in shades of white, brown and indigo. They can be distinguished from other West African robes by their distinctive front pockets and their overall design – according to Venice Lamb there were two styles: a simple sleeveless tunic called in Sierra Leone kusaibi, and a more complex sleeved robe called a duriki ba. A very few surviving examples (two of which we looked at) were embroidered and fall into a group that Bernhard Gardi in his important book Le Boubou – c’est chic calls Manding robes.

However there remains an even smaller number of robes from the same region tailored from the elaborately patterned kpoikpoi cloths for which Sierra Leone weavers were so notable. This robe, part of the British Museum’s Beving collection, was collected at least by 1913 and most probably dates from the second half of the nineteenth century. It was apparently (Lamb 1984:136) collected in Bonthe region, Sierra Leone. It is among less than ten robes I am aware of that have been made from kpoikpoi cloths.

The structure is simple – an existing small cloth is simply folded in half width ways, a neck hole made, and a patch pocket added at the front. This results in a robe made up of seven strips of cloth, each around 18cm in width, and a total size of 124 cm width by 96cm length. The pocket is made from a square piece of cloth, one and a half strip widths in size, with the small corner fold typical of robes from the region. The lower half of each side is sewn up with the rest left open to create armholes. However in marked contrast to this simple tailoring the cloth used to create this robe is exceptionally elaborate. On the pocket detail above we can see blocks of thicker indigo dyed thread inserted as supplementary weft floats half way across the strip in sufficient quantities to distort the flow of the ground weft into a curved pattern. This is just one of the many variations used in a way that seems to me to suggest a deliberate echo of the embroidery patterns normally found on the pocket and chest areas of prestige robes. In particular when we look at the back of the robe we see that the small block of checkerboard pattern largely concealed by the pocket is repeated.

Elsewhere we see the use of tapestry weave techniques to create distinctive triangular patterns that are a feature of the more complex styles of Sierra Leone weaving.

The detail above from the lower left of the back also shows some of the remarkable variation in weft stripe placement and simple variants of the weft float patterning the weaver has utilised. To me though the most interesting feature, and the strongest evidence that this cloth was woven to order with its use as a robe planned is the contrast in colour between the front and the back. On the front of the robe white is the dominant colour, but on the back there is a preponderance of light blue indigo dyed thread. The pattern diverges at the fold in the centre of the cloth, yet the strips used are continuous, strongly suggesting that it was woven with this use in mind. We can see this in the photograph below where the two sides are shown together (please excuse the inept photoshop.)

Can anything useful be said about the ethnic origin of this robe ? Venice Lamb published it (1984:137) with a caption ascribing it to the Vai ethnic group, but in the text is much less certain noting only “It is possible that this garment is an example of Vai inventiveness in weaving.” However I am not convinced that there is sufficient evidence to distinguish Vai weaving from that of the larger group of Mende weavers. Easmon (1924:22) noted that kpoikpoi cloths were “essentially a Mende cloth, and is also made by the Gallinas [Vai]”. Very few of the small number of early Sierra Leone cloths in museum collections have any detailed collection data and where they do it is not generally sufficient to confirm that the piece was woven in the same place as it was collected. Prestige cloths and prestige robes were important trade goods and may well have been traded a considerable distance from their place of origin. Bonthe, where this cloth was collected, was mainly inhabited by Sherbro people . We might also note that the whole process of assigning a particular cloth style to a particular ethnic group is extremely problematic.

All photographs above by Duncan Clarke. Click on the photos to enlarge.