Thursday 31 December 2009

Tuesday 29 December 2009

Some field photographs

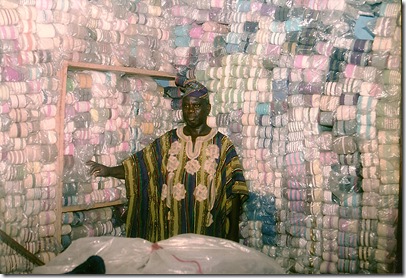

The master weaver and cloth dealer Alhaji Kegunhe in his shop, Iseyin, Oyo State, Nigeria. 1997. Recently published in B.Gardi ed. "Woven Beauty: The Art of West African Textiles." (Basel, 2009) Iseyin is one of the two main centres of Yoruba aso oke weaving and the Alhaji was one of its most successful weavers and dealers. Each bag contains sufficient cloth strips to be sewn up to make a woman’s wrapper skirt, shawl, and headtie, an outfit known as a “complete.”

Every four days before dawn in Okene market, Kogo State, Ebira women weavers display their completed cloths for sale folded in piles on their heads. Okene, circa 2002. Today Okene is the main centre for women’s weaving on the upright single heddle loom in Nigeria, with several thousand active weavers producing shiny rayon shawls in a variety of patterns which can be found on sale as far afield as Accra.

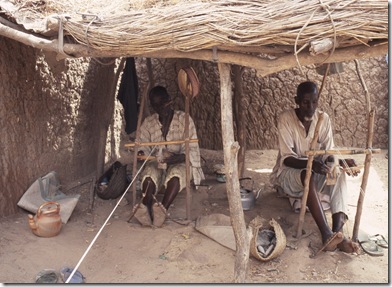

Hausa men weaving white cloth in strips 1cm in width. The completed strips will be sewn together edge to edge to make veils and robes, dyed dark indigo, then exported to Tuareg peoples in Niger and Mali. Kura, Kano State. Nigeria 2005. These are the narrowest strip of cloth woven in Africa and are among the most expensive of locally produced textiles. The production of this cloth for export to the peoples of the Sahara was once the main industry of Kano but today only a few skilled practitioners remain.

A pair of Hausa cloth beaters at work in the village of Kura. Completed and dyed veils are beaten with a mix of powdered indigo, goat fat, and water that imparts a metallic dark blue sheen. The cloth will be folded over into ever smaller sections and beaten repeatedly until the tightly pressed cloth forms a solid rectangular block about 30cm long. It is then wrapped in brown paper for sale. These two men are among the last remaining exponents of an ancient and highly skilled craft. Kura, Kano State, Nigeria, 2005.

A Nupe woman weaver at work in her husband's family compound, Lafiagi, Niger State, Nigeria, 2006. Unlike the Ebira, Nupe women weave mainly for local and family use and their cloths are rarely found for sale elsewhere in Nigeria or neighbouring countries.

Click on any image to enlarge. All photos copyright Duncan Clarke. Do not reproduce without permission.

Monday 21 December 2009

Emile-Louis Abbat sur le Soudan Francais 1894-98

| A page from the albums of annotated photographs taken by Emile-Louis Abbat in French Soudan. (copyright Catherine Abbat. Do not reproduce without permission.) |

Fascinating new site displays 450 photographs with captions and 89 letters to his family left by Emile-Louis Abbat, a lieutenant in French Soudan (today Senegal, Mali, and Burkina Faso.) In addition to two of the earliest images of Malian weavers the first album includes rare views of a man wearing a lomasa boubou, another wearing a boubou tilbi, and a wonderful photo of a camel transporting two massive wheels of strip woven cloth.

“Emile-Louis ABBAT a été lieutenant au Soudan Français de 1894 à 1898. Il a laissé de cette période 450 photographies légendées (Sénégal, Mali et Burkina Faso actuels) et 89 lettres à sa famille, ainsi que plusieurs rapports militaires et une planche de dessins de scarifications. L’ensemble a été numérisé par mes soins.

La complémentarité iconographique et épistolaire du fonds en fait un témoignage exceptionnel sur cette page de l'histoire coloniale : les actions militaires bien sûr, mais aussi les relations entre les populations, les modes de vie, les métiers, la géographie, l’agriculture, et bien d’autres thèmes encore. Ce site se propose de le faire connaître.” Visit the site here

Adire African Textiles archive – Ewe cloths now online

One of the best ways to learn about a particular art form is to study numerous examples and familiarise oneself with variations in form and style. African textiles are in the main not well documented and it can be hard to find a good range of images online. Many major museums are in the process of making their collections accessible online and we will be reviewing some of these in subsequent posts. As our contribution to this process and as an educational resource, over the next few weeks we will be posting on line sections of our own archives. The first of these is a large selection of vintage Ewe cloths that have passed through our hands over the past decade. This part of the archive currently totals 625 photos that represent what seemed to me at the time to be the best and most interesting examples of Ewe weaving – in other words there are a lot of more ordinary pieces out there which I did not buy and therefore are not included here. Most date to between 1900 and 1950. The majority of these cloths are now in private or museum collections so please do not reproduce them without permission. Click here to view. If you are interested in the selection of Ewe cloths we have for sale at present please click here.

Strip Weave Cloth Sample Packs

Over the years a number of people have asked us for packs of sample pieces of strip woven cloth. These are a good educational resource providing a way to learn about patterns, techniques etc, as well as a useful source for collectors, quilters, and textile artists. We can put together mixed packs of strip pieces of average length about 10ins/25cm to include Asante and Ewe kente, Yoruba aso oke and others. Cloths will date from 1900 to 1990s, with most before 1950. These will be similar but not identical in content to the one illustrated. More details here

Friday 18 December 2009

New Book on photography in Central Africa

| Auguste Bechaud – Photographe-soldat en Afrique centrale by Didier Carite (Le Portfolio, 2009) |

This is an important and interesting addition to the growing body of literature on early photography and postcards in Africa. Includes fascinating images of dress, tattooing, and body decoration among the Sango, Ngbugu, Yakoma, and other Central African peoples at the start of the C20th, along with some other more disturbing photographs such as the aftermath of an elephant hunt.

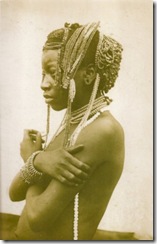

| Young woman of the Gbanziri |

| Femmes d’europeans |

I was particularly pleased to learn more about the origins of the above image because it has intrigued me as a postcard for some time. The lady on the left (click on the photo for a larger view) is wearing an especially elaborate strip woven wrapper cloth that certainly was not produced in central Africa. Last year in Basel Bernard Gardi and I disagreed about its origins – he thinks it is from Sierra Leone, where Mende and Vai weavers do produce cloths with blocks of oval cell-like float patterns as seen here. To me though, it looks like the work of Jukun or related weavers in the Benue valley of eastern Nigeria – they also wove the “cell” pattern but additionally the weft stripes framed by lines of weft floats. Either way it has clearly travelled far from its origins, providing a salutary reminder of the mobility of prestige textiles within Africa in the early colonial period.

The book should be available from amazon.fr or Soumbala or failing that direct from the author. Contact me for his email.

Thursday 17 December 2009

Artistes d'Abomey at musee du quai Branly

Until 31 January 2010 there is a superb exhibition at the musee du quai Branly, Paris, focussing on the court artists who supplied the dramatic sculpture, banners, robes etc. to the powerful Fon kingdom at Abomey in the Republic of Benin. Alongside iconic statues such as the celebrated royal "bocio" figures the exhibition provides African textile enthusiasts this provides a rare opportunity to see part of the worlds two major collections of the celebrated Fon appliqué banners, including some examples (not shown here) presented by the Fon king to the French Emperor Napoleon III in 1865.

Until 31 January 2010 there is a superb exhibition at the musee du quai Branly, Paris, focussing on the court artists who supplied the dramatic sculpture, banners, robes etc. to the powerful Fon kingdom at Abomey in the Republic of Benin. Alongside iconic statues such as the celebrated royal "bocio" figures the exhibition provides African textile enthusiasts this provides a rare opportunity to see part of the worlds two major collections of the celebrated Fon appliqué banners, including some examples (not shown here) presented by the Fon king to the French Emperor Napoleon III in 1865.

There is an interesting booklet "Artistes d'Abomey" (Beaux Arts editions) that accompanies the show, and a catalogue with the same title that appears not yet to be available. More info here.

Wednesday 16 December 2009

Tuesday 15 December 2009

More Nigerian Textiles...Jukun, Gwari, Yoruba

Just back from a brief trip to Nigeria...

Some of the new posts from our website

PRICE: US$675

Measurement: 84ins x 50ins, 214cm x 127cm

Typical example of the elaborate and complex supplementary weft float patterning once practised by weavers of the Jukun people of the Benue valley in Eastern Nigeria. Collected some years ago in the vicinity of the Jukun capital of Wukari. Jukun cloths are not well documented and are rarely available on the market. This piece is in excellent condition and dates from 1950-60. It may be compared to a piece collected in 1965 illustrated in Sieber "African Textiles and Decorative Arts" (MOMA 1972 page 188.)

PRICE: US$1100

Measurements: 78ins x 57ins, 198cm x 144cm

Superb and rare early C20th woman's wrapper. Each strip combines fine hand spun indigo checked "etu", "guineafowl pattern," with magenta "alaari" - silk from the trans Saharan trade. It would have been an extremely expensive and prestigious cloth in its day. In searching for these early cloths I look for pieces where all the original hand stitching is intact, as here. After almost a century many have begun to come apart at the seems and been restitched using a sewing machine, often in a less than careful way. Intact pieces like this have a pleasing completeness but are extremely rare. Dates from circa 1900-1920 and is in excellent condition.

PRICE: US$785

Measurement: 65ins x 32ins, 164cm x 81cm

Woman's wrapper from the Gwari people of central Nigeria - the once obscure and remote Gwari ancestral homeland is now the site of the modern Nigerian capital of Abuja and many Gwari farmers have been displaced. These are among the strangest cloths to be found in Nigeria. Woven for the Gwari by weavers of Hausa ancestry the hand spun indigo dyed strips have regular rows of open work, broken up at a few places by blocks with a different openwork arrangement. The woven strips are then joined using a complex braiding technique that adds a long narrow open area between each strip except at the lower edge. This treatment of strips is as far as is known, unique to the Gwari. It creates a strange highly textural cloth that is oddly appealing. In excellent condition dates from around mid C20th or earlier.

Wednesday 25 November 2009

Hand woven textiles in Cote D'Ivoire today..

Côte D’Ivoire is home to a fascinating diversity of textile production traditions, the vast majority of which have hardly begun to be researched. Aside from the tie dyed raffia cloths of the Dida people, most of which incidentally are actually very newly made for export sale, the collectors' market has paid little attention to Ivoirian fabrics. Over the past decade the Civil War and the uneasy peace in a divided country that has followed have made further research difficult or impossible. For this reason I was very interested in the glimpses of contemporary cloth production and use provided by the photos and short texts in a newly published book. Somewhat misleadingly titled "Arts au feminin en Côte D’Ivoire", edited by Philippe Delanne, (le cherche midi, Paris, 2009) this is a glossy government endorsed survey subsidised by the UNFPA. Alongside printed fabrics it shows people at celebrations and events wearing a wide variety of locally woven cloths. By the far the most widely illustrated are modern Baule ikat dyed cloths as shown in the first photo.

Côte D’Ivoire is home to a fascinating diversity of textile production traditions, the vast majority of which have hardly begun to be researched. Aside from the tie dyed raffia cloths of the Dida people, most of which incidentally are actually very newly made for export sale, the collectors' market has paid little attention to Ivoirian fabrics. Over the past decade the Civil War and the uneasy peace in a divided country that has followed have made further research difficult or impossible. For this reason I was very interested in the glimpses of contemporary cloth production and use provided by the photos and short texts in a newly published book. Somewhat misleadingly titled "Arts au feminin en Côte D’Ivoire", edited by Philippe Delanne, (le cherche midi, Paris, 2009) this is a glossy government endorsed survey subsidised by the UNFPA. Alongside printed fabrics it shows people at celebrations and events wearing a wide variety of locally woven cloths. By the far the most widely illustrated are modern Baule ikat dyed cloths as shown in the first photo.

The Baule are an Akan people who migrated to their present location in central Côte D’Ivoire from Ghana in the C16th but seem only to have learnt weaving from their Dioula neighbours in the early to mid C20th. Note the standing posture of the weavers in the photo, unlike the seated style of the Asante and Ewe in Ghana. The book notes that there are around 300 weavers in a cooperative group in the village of Bomizambo 45km from Yamoussoukro.

In contrast to the Baule, the weaving of the Dan people in the central western part of the country is very obscure. Perhaps surprisingly given the attention paid to Dan masks and sculpture I am not aware of any published images before this that show Dan textiles and weaving.

In contrast to the Baule, the weaving of the Dan people in the central western part of the country is very obscure. Perhaps surprisingly given the attention paid to Dan masks and sculpture I am not aware of any published images before this that show Dan textiles and weaving.

For a selection of our vintage textiles from Côte D’Ivoire see here and for further reading see here

Tuesday 17 November 2009

The "Spotted Hyena" - Dioula ikat weaving in northern Ivory Coast

A Dioula weaver at work in the square beside the mosque, Bobo-Dioulasso, Burkina Faso. Vintage postcard, circa 1910, author's collection.

A Dioula weaver at work in the square beside the mosque, Bobo-Dioulasso, Burkina Faso. Vintage postcard, circa 1910, author's collection.

"Elegantes de Kong" (Prouteaux 1925, p.608)

An elderly Dioula weaver, Dar Salami, south Burkina Faso, 2004 (auther's photograph.)

Thursday 22 October 2009

Fante Asafo Flags - real or fake? - old or new ? - part two

A genuine Fante Asafo flag from our gallery, age circa 1920-40. Illustrates the proverb "we control the rooster and the clock bird", i.e. we are so strong that we can even control time.

A genuine Fante Asafo flag from our gallery, age circa 1920-40. Illustrates the proverb "we control the rooster and the clock bird", i.e. we are so strong that we can even control time.

This is an authentic, well made and designed post-Independence flag from the collection of the Textile Museum, Washington. It illustrates the boast " We can carry water in a basket using a cactus as a head cushion" i.e. "we can do the impossible."

Wednesday 21 October 2009

Fante Asafo Flags - real or fake? - part one

A high percentage of the Fante Asafo flags for sale on the net are recently made copies or "fakes." Today's post (a flag from a private collection in Italy, circa 1930-40s) is a quick reminder of how wonderful genuine flags from the Fante Asafo societies can be. I am working on a longer post on this subject but in the meantime for further info see here and here..

Friday 16 October 2009

Couverture Personnages - strip woven wedding hangings from Mali

In the 1950s large brightly coloured blankets called tapis with solid blocks of colour began to be a fashionable gift at weddings, beginning to displace older traditions of indigo blue and white cotton and brown wool blankets. They were used to adorn the walls of the house during weddings and as covers for the newly imported iron beds. At some point in the 1960s one master weaver called Abdurrahman Bura Bocoum reconfigured this new style of coloured blankets so that the weft blocks depicted large figures of humans and animals. Soldiers became the predominant theme of these cloths following the military coup in Mali in 1968. It is not known when he died, but Bocoum was succeeded by at least three other weavers. One of this second generation, also now dead, was Mama Diarra Kiba, who wove the yellow ground cloth shown above, which is now on our website here.

This piece with thinner, arguably cruder, figures is by Jaara Ila Jigannde.

The best known of this second generation of weavers is Oumar Bocoum, shown here. Now an elderly man who no longer weaves, his work featured in the African Textile exhibition at the Barbican Art Gallery, London, and at the Kennedy Center in 1995. The remaining cloths shown here are a selection of typical Oumar Bocoum pieces. They would have been commissioned from the weaver as prestige hangings for display during a wedding, then later sold. We also have a Bocoum blanket at our gallery - more details here. For more information see Bernhard Gardi ed. "Woven Beauty: The Art of West African Textiles" (Basel, 2009).

Wednesday 14 October 2009

A Nupe woman weaver.

Wednesday 7 October 2009

Beyond the Kuba in Congo surface design