Some African textile scholars have remarked on what they perceive to be affinities between aspects of African textile design and the use of “off beat” rhythm in African musical traditions, for example in designating certain types of Malian blanket as “jazz cloths.” While these analogies are suggestive and thought provoking, and do seem to me to point in some degree towards important aspects of textile design in the region, as yet there has been very little attention paid to discussing these issues with either makers or consumers of particular African textile traditions. In this note I want to quote at some length from a recent article by the Ghanaian professor of literature Dr Kofi Anyidoho (“Ghanaian Kente: Cloth and Song” in The Poetics of Cloth: African Textiles/ Recent Art edited by Lynn Gumpert, GreyArt Gallery, New York, 2008) , that mentions neither “off beat” rhythm nor “improvisation,” but nevertheless appears to me to be an important contribution to this discussion by someone who is both an Ewe and a trained weaver.

“The first expert on kete weaving I interviewed was my uncle Dumega Kwadzovi Anyidoho, the man who brought me up and under whose tutelage I learned to weave. Now in his eighties, he is acknowledged as one of the most experienced master weavers in Wheta, with more than sixty-five years of experience. He is also a master drummer and heno (poet-cantor.) Halfway through our conversation I asked him to name other great master weavers he could recall. To my surprise, almost everyone he remembered was also a heno and/or a master drummer….

My uncle pointed out that this was more than a coincidence and offered two possible explanations for this apparent connection between the art of the master weaver and that of the master drummer and the poet-cantor. First, he explained that the weavers, whether alone or in groups, often sang to ease the tedium of long hours at the loom. Of greater significance however, is the fact that weaving, like drumming and singing, is a rhythm-based aesthetic performance. From the habit of singing songs composed by others, the musically and poetically gifted among the weavers would begin to try out their own voices and, over time, developed into composers of note. The rhythm maintained by the regular alternation of the heddles (eno) and the treadles (aforke), reinforced by the throwing and catching of the shuttle (evu), as well as the constant rhythm of the beater (exa), all provide a natural drive for the flow of song….

Beyond the aesthetic competence entailed in the application of the rhythm of weaving to the composition and performance of song, there is the more complicated factor of technical competence. Weaving is more than the application of a sense of rhythm. It requires considerable technical skills in design, possible only through a careful application of mathematical calculations combined with the architectural ability to construct organic shapes and forms from individual threads as building blocks. This process is not unlike that involved in the architectural design of the well-made song or poem.”

Click on any of the images above for a larger view.

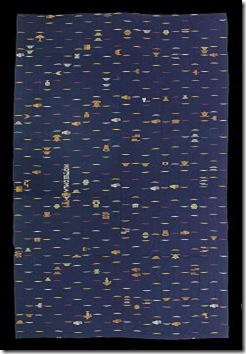

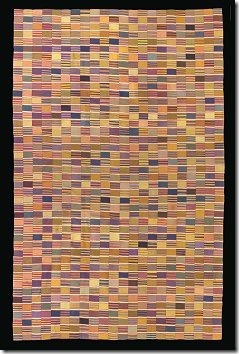

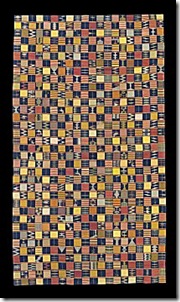

To conclude, follow the links by clicking on any of the Ewe cloths below to view a selection of top pieces from our gallery. Looking at and thinking about the design of these cloths in terms of rhythm and structure does appear to enhance perception of the designs….