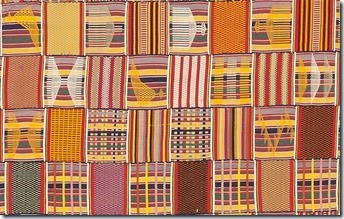

In today’s post I will be taking a look at two extraordinary Asante silk kente men’s cloths and airing some preliminary thoughts and queries that they suggest in relation to creativity and innovation. The first, above, a predominantly green version of the classic “a thousand shields” design, is from the William Itter Collection in the USA . The second, below, that we found recently and is now in a UK private collection, is a warp stripe patterned cloth called “Ammere Oyokoman” in the familiar red green and gold colours so favoured by Asante weavers. Both cloths are woven from silk and both can be assumed to date to the first third of the C20th.

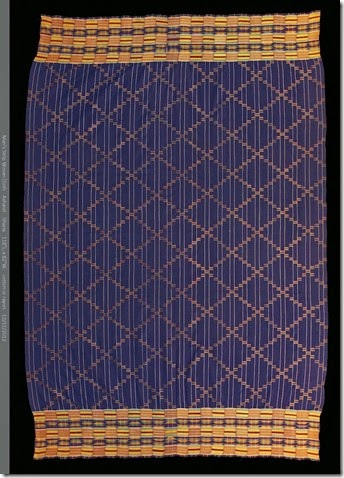

Looking first at the green cloth, on first glance it appears to be a standard version of a familiar design, such as the cloth, also from the William Itter Collection, below.

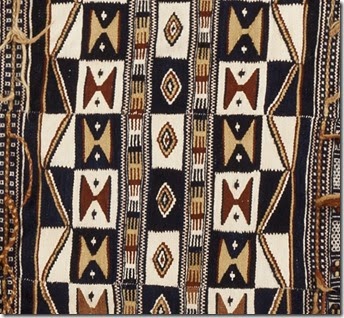

The diagonal grid pattern in the main field of the cloth is made up of small rectangles, recalling the rectangular shape of the wood and leather shield once used by Asante warriors and giving the cloth its name Akyempem, or “a thousand shields.” Incidentally the vast majority of Asante kente cloths were named after the warp stripe pattern, this is an exception. However the technique used is quite different as detail photos show:

Compare the usual version, above, where a supplementary weft float in red and yellow on a blue and white warp striped, warp faced background, is used to create each rectangle in the grid of “shields”, with the one below:

Here the entire cloth is weft faced and the grid of red and yellow shields is created as weft faced rectangles using a tapestry weave technique. I can’t recall another example of a fully weft faced Asante kente and I have certainly never seen tapestry weave used in this way. Also very unusual is the background colour that alternates picks of yellow green and blue that blend to a muted green overall effect. These threads are not plied together to create a “tweed” in the way that Ewe weavers sometimes do. We should also note that using this technique to reproduce the design would have been both significantly slower (as more weft threads and hence more weft picks are required) and, because it needed far more thread, considerably more expensive that the standard method.

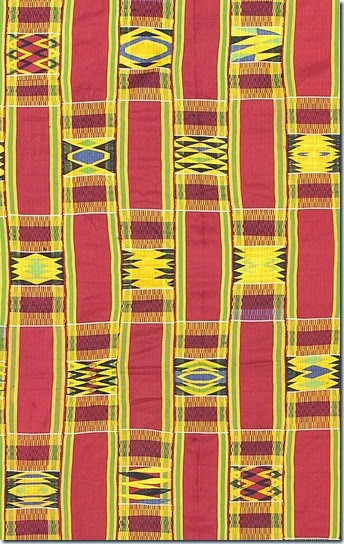

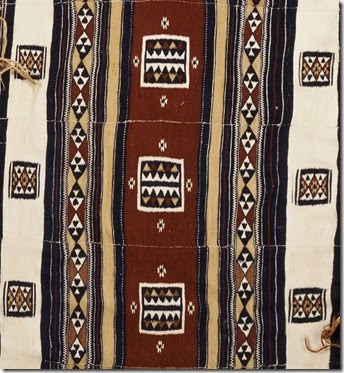

Turning to the red Oyokoman cloth, here the notable feature is a large array of unique weft float patterns.

The grid framework imposed by the interaction of warp and weft threads naturally leads itself to the creation of diamonds, triangles, and regular stepped patterns and Asante kente weaving exploits these shapes to the full. Here though the master weaver has transcended the limitations of the form by weaving ellipses and even circles, as well as fragmenting the standard diamond shapes to create more complex composite motifs.

While my primary purpose here is simply to register, share, and admire these two wonderful cloths, to me they also raise a number of interesting questions about innovation and creativity in kente weaving and perhaps pose a challenge to any over simplistic contrast between creative expectations expressed in Asante as opposed to Ewe textiles. Anyone familiar with the two genres is aware that there is a greater variety of styles and techniques apparent in “Ewe kente” than in Asante. As William Itter noted in our discussion of these two cloths “regarding the controlled or restrained composure of construction and design found in Asante cloth from the more expected/unexpected variety of design in Ewe wraps.”

Here we have seen two superb examples of novel and innovative extension of established techniques that nevertheless remain within the expected parameters of Asante kente design in terms of cloth layout, overall patterning etcetera. Such cloths, I would suggest, arise out of a sustained interaction between an experienced master weaver and a exceptionally well informed and perceptive patron, in this context we might suppose an Asante king or senior chief with a deep knowledge and understanding of the existing pattern repertoire who is able to finance and encourage such sophisticated results over a considerable period. This hypothesis would fit with what little we know from the unfortunately rather inadequate ethnographic documentation of Asante kente production for royal patronage in weaving villages such as Bonwire. It would however, in my view, be over simplistic to contrast this with a more open pattern of patronage for Ewe cloths as alone explaining their greater variety. I will return to this complex topic in future posts.

I am very grateful to William Itter for generously sharing his photographs. My thanks also to the owner of the Oyokoman cloth. Click on the images to enlarge.