African Textiles Today by Chris Spring (British Museum Press), shifts the focus away from the woven textile traditions of West And Central Africa that dominated the museum’s classic but now over two decades old, African Textiles by John Picton and John Mack. Instead Spring devotes the largest part of the book’s colourful selection of images and comparatively brief and accessible texts to printed textiles, notably to the so-called “wax” and “fancy print” styles of West and Central Africa and especially to the “kangas” and related cloths made for the Eastern and Southern African markets. This shift mirrors a broadening in the British Museum’s acquisition and displays over recent years to encompass these previously neglected areas.

Kanga, Tanzania, 1960s. Af2003,21.1 : “The inscription, in Kiswahili written in Arabic script, reads: You left the door open, so the cat ate the doughnut; what are you going to do about it, tenant ?” page 190.

Rather than attempting an encyclopaedic survey of the myriad of textiles produced in Africa over recent decades, the book sets out a number of themes, including trade, status, communication, and systems of belief, illustrating them with brief “stories” based on individual textiles and drawn widely from across the continent. Other chapters look at the currently fashionable engagement between textiles and a number of contemporary African artists (a topic that provides the front cover image of an El Anatsui sculpture) and at textiles in photography (the back cover image of Samuel Fosso as a parody Congo chief.) Drawing on his research and publications on topics including kangas, contemporary African art, and the textile traditions of North Africa, Chris Spring is able to highlight interesting and often unexpected parallels between diverse artefacts and traditions.

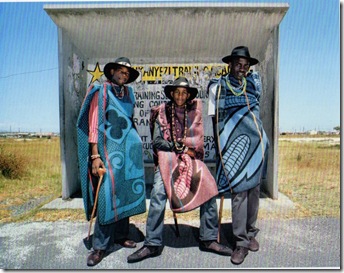

A New Beginning by Araminta de Clermont, Cape Town, South Africa, 2009-10. South Sotho men – “These three young men wear another kind of blanket known as lekhokolo, which shows that they have completed the initiation ceremony and reached manhood. Designs such as the maize cob or Poone, seen here on their Seana Marena label blankets, are very popular for lekhokolo, as they signify virility and fertility.” page 228.

Although some fine and historically significant objects from the British Museum’s collection of West African textiles are illustrated and discussed, I would have liked to see a book with this title pay more attention to developments today in the still vibrant historical textile traditions of West Africa, where significant innovation is apparent in both weaving and dyeing of cloth in many areas. Nevertheless it is African printed textiles that have in recent years been at the heart of a growing appreciation of African fashion and of a growing recognition of the work of African fashion designers. In exploring the British Museum’s expanded collection activities in this field, and in concluding with the work of Duro Olowu, a leading Nigerian born fashion designer, Spring’s lively book looks ahead to new directions in this fascinating and still under- researched field.

![313285_190400007701425_925494034_n[3] 313285_190400007701425_925494034_n[3]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEjokADdvU7Xv8prwtaPJC6F9bMzU3xI16Ug-YZzPet2GE4mLyK6UCJd9sUCybg31z7hPW1L-LHHtyWVQip86R8hnm0SShwJuH3rJM_SCaXbnXwH3nLajxgDNtHci4WQT7edUn0Y0SDyZnCl/?imgmax=800)