Some especially interesting comments on textile use by the eminent historian Phyllis M.Martin.

“Kristen Windmuller-Luna: In your essay in the exhibition catalogue, you write extensively about cloth's role in the Loango economy. How did that system function?

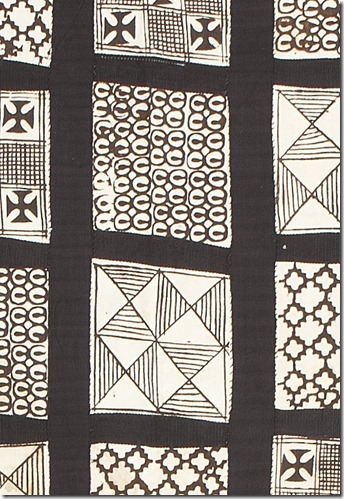

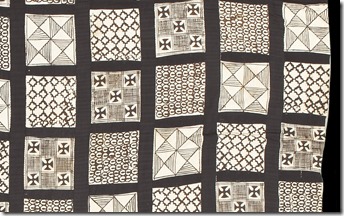

Phyllis M. Martin: We have to consider that cloth is a way of storing value. Cloth was also an essential ingredient in society and culture. It was not just a piece of fabric with wonderful weaving and designs; it was much more than that. When the Dutch arrived around 1600, they talk about how the king—the Maloango—had warehouses and storehouses bursting with cloths, copper, and ivory.

And so you ask, "Why cloth?" Cloth has many advantages, and we can think of it functioning like a currency; a currency needs to be portable, it needs to be durable, and preferably it needs to be locally produced. The region was described in one late sixteenth-century source as "the land of palms," which was important because raffia palm trees provided the raw materials which weavers then made into threads to create these textiles.

Kristen Windmuller-Luna: Where would the textiles included in the exhibition, which are all luxury items, have fit into the Loango economy?

Phyllis M. Martin: The Maloango and other wealthy and powerful persons controlled the production of cloth. There were certain gradations according to the labor and creativity involved in their production. The Maloango had control over master weavers, and only they were allowed to produce these incredibly high-value, beautiful pieces. There were four or five gradations of fabric, and commoners would wear very simple cloth. When you're exchanging goods, obviously, this kind of luxury cloth is very high value, so it could be used as a currency—it's like a one- or ten- or a hundred-dollar bill. Several could be used together to vary the value in an exchange. A common person might be wearing just a very basic weave—no colors, no design. In our society we also measure people by the clothes that they're wearing; it's of course much of the same thing. There are many commonalities with European society when you stop to think, especially at this time [the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries].”

excerpted from:

The Visual Archive: A Historian's Perspective on Kongo and Loango Art

Kristen Windmuller-Luna, 2015–16 Sylvan C. Coleman and Pamela Coleman Memorial Fund Fellow, Department of the Arts of Africa, Oceania, and the Americas; and Phyllis M. Martin, Professor Emeritus of History at Indiana University Bloomington