On my recent visit to Ghana I was pleased to find this remarkable wool and cotton cloth from Mali, collected by one of my contacts from the chief of a small village in the north west of the country. Itinerant traders from Mali have been selling cloths in Ghana and neighbouring countries for at least 500 years so the presence of this cloth was not too surprising in itself. Wool blankets from Mali have become an accepted part of the court regalia of many Ghanaian chiefs, used for a variety of purposes including lining ceremonial hammocks and palanquins, covering royal drums, and just as a backdrop for displays of the royal treasures.

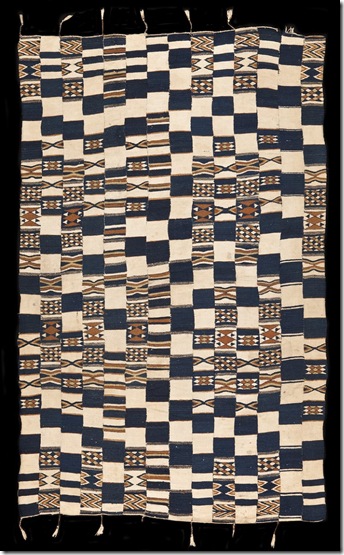

The surprising, and to my knowledge, unique aspect of this particular cloth is the design and layout. Made up of 14 strips of approximately 3 1/2 inch width (9cm), squares of indigo blue dyed wool alternate with squares of white handspun cotton, serving as a backdrop for quite complex patterning in natural brown dyed wool executed using a tapestry weaving technique, these strips would normally have been laid out in a much more regular fashion to form a far larger cloth, called an arkilla jenngo.

Arkilla jenngo were, according to Bernhard Gardi, woven in the area west of Tomboutou near Lake Faguibine by Songhay-speaking weavers, primarily working for Tuareg patrons. Interestingly he notes that according to his informants this type of wool blanket was not traded to Ghana. They were used as highly prestigious tent hangings for high status weddings.

Photo above by Harald Widmer, January 1952. The names given to the motifs “reflect the significance that weddings and bride wealth have in social life: we have for example, ‘cushion’, ‘bedposts’, ‘money’, ‘board game’, ‘leather fringe’, or ‘calabash’. (Gardi 2009.)

Turning back to our cloth we can now see that the standard strips woven for an arkilla jenngo have been put together in a different and unexpected way, with the regular layout of the traditional form replaced by an apparently random placement creating an “offbeat” staggered overlap and contrast between each strip and an overall dynamic oscillation across the cloth. How can we tell that this was a deliberate effect and not just the random result of a partial or damaged arkilla being re-purposed by someone unfamiliar with the tradition ?

If we look at the ends of the cloth we see that it was carefully finished with a braided wool cord making up a series of tassels. This was the normal technique in Mali for finishing a smaller type of wool blanket known as a kaasa, and clearly shows that this cloth was assembled by someone working within that tradition. So we can only speculate on why this novel layout was adopted and it remains a mystery.

No comments:

Post a Comment