Below is an excerpt from the section on important textile traditions covering Asante kente cloths:

Asante Kente Cloths

Kente is the best known and most widely appreciated of all African textiles, adopted throughout the African diaspora worldwide since the 1960s as a symbol of Pan-Africanism and Afrocentric identity. At the same time it continues to play a vital living role in the culture of its creators, the Asante (Ashanti) people of Ghana in West Africa. The story of kente is closely interwoven with that of the Asante Empire and its' Royal Court based at Kumase, deep in the forest zone of southern Ghana. One of the first accounts of Asante royal silk weaving comes from the 1730s when a man sent to the court of King Opokuware by a Danish trader observed that the king "brought silk taffeta and materials of all colours. The artist unravelled them ....woollen and silk threads which they mixed with their cotton and got many colours." Silk was also imported into Asante from southern Europe via the trans-Saharan caravan trade. Many kente cloths utilised silk for a range of decorative techniques on a background of warp-striped cotton cloth, but some of the finest cloths prepared for royal and chiefly use were woven wholly from silk. Although since the early decades of the C20th natural silk has been mostly replaced with artificial "rayon" fibres, the artistry of Asante weavers has continued to produce remarkably beautiful cloths.

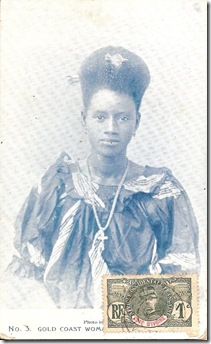

Asantehene Agyeman Prempeh I wearing an Oyokoman kente cloth. 1926. Vintage postcard, author's collection.

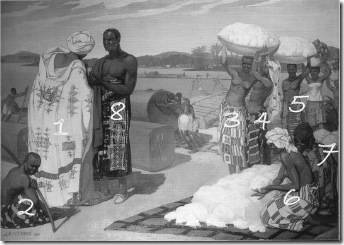

The cloths woven in the nineteenth century for the court of the Asantehene, the king of the Asante empire were probably the ultimate achievement of the West African narrow-strip weavers art. The raw material for this artistry came from Europe in the form of silk fabrics which were carefully unpicked to obtain thread which could then be re-woven into narrow-strip cloth on looms that utilised two, and in some cases even three, sets of heddles to multiply the complexity of design. The king's weavers were and still are grouped in a village called Bonwire near the Asante capital of Kumase, part of a network of villages housing other craft specialists including goldsmiths, the royal umbrella makers, stool carvers, adinkra dyers, and blacksmiths. One Asante weavers' origin myth recalls that the first weaver, Otah Kraban, brought a loom back to Bonwire after a journey to the Bondoukou region of Côte D'Ivoire. An alternative legend recalls that during the reign of Osei Tutu the first weaver learnt his skill by studying the way in which a spider spun its web. The spider, Anansi, is an important figure symbolising trickery and wisdom in Asante folklore. Away from the court cotton weaving supplied much of the everyday dress for the Asante people, in the form of striped cloths, mostly of indigo blue and white, until it was largely displaced by wax prints and other imported textiles in the present century.

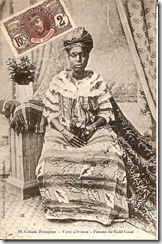

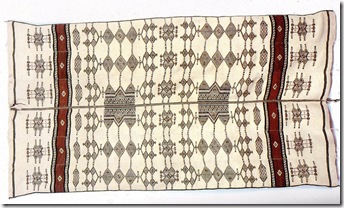

Silk man's kente in the "gold dust" pattern, early C20th

In many kente cloths the design effect is achieved by the alternation of regularly positioned blocks of pattern in bright coloured silk with the more muted colours of the warp-striped plain weave background. Interestingly it is the background designs, the configurations of warp stripes of varying widths, that provide the basis for most pattern names. As might be expected in a culture so interested in proverbs and verbal wordplay there is a large vocabulary of pattern names still remembered by elderly weavers. Some of these names, such as Atta Birago and Afua Kobi, refer to the individuals, in these cases two Queen Mothers, for whom the designs were first woven. Others refer to historical incidents, to household objects, to proverbs, or to certain circumstances of the cloths use.

Kente cloth weaver, early C20th postcard.

Most designs are produced by combining two distinct decorative techniques. The first, supplementary weft float, involves the addition of extra weft threads that do not form part of the basic structure of the cloth. Instead they float across sections of the ground weave, appearing on one face of the cloth over maybe six or eight warp then crossing through the warp to the back, floating there, then returning again to the top face. Rows of these wefts are arranged to form designs such as triangles, wedges, hour-glass shapes etc. Asante weavers distinguish loosely spaced floats, which they call "single weave", from more densely packed designs that conceal the background completely and are known as "double weave." The second effect is to create solid blocks of coloured thread across the cloth strip entirely concealing the warp. Without dwelling too much on the technicalities, this effect is achieved by the use of a technical innovation unique to the weaving of southern Ghana, namely the use of a second set of heddles that has the effect of bunching together groups of warp threads allowing them to be hidden by the weft. The design of most kente cloths involves framing areas of weft float decoration within the narrow solid bands called bankuo. The finest and most elaborate examples of this style and perhaps the most spectacular cloths ever woven in Africa, completely covered the underlying warp design with alternating sections exploiting the full range of weft float designs between very narrow bands, producing a cloth named Adwinasa, meaning "fullness of ornament."

Further Reading:

Adler,P. & Barnard,N. African Majesty (1992) - illustrates a great collection.

Clark Smith, S. "Kente Cloth Motifs" African Arts 9(1) (1975)

Lamb,V. West African Weaving (1975)

Menzel, B. Textilien aus Westafrika (1972)

Ofori-Ansah,K. Kente is more than a cloth (1993) - influential poster with interpretation of pattern meanings.

Rattray, R. Religion and Art in Ashanti (1927)

Ross,D. Wrapped in Pride: Ghanaian Kente and African American Identity(1998)

Click on the image to go to our gallery of Asante kente cloths for sale.

Back to African Textiles Introduction