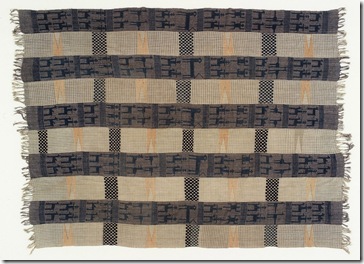

“Commemoration and Education wall”, photo copyright Barbara McCann, please do not reproduce without permission. Click for a larger view.

“In late 2008, I received an email from Barbara McCann, pitching an exhibition to Carleton University Art Gallery (CUAG) of African textiles drawn from her extensive personal collection. Fresh from its successful exhibition at Nova Scotia College of Art and Design, she was excited about showing the collection in Ottawa, where she and her husband Bill have long lived.

Like all exhibition proposals, of which the gallery receives many, we weighed this one carefully. The McCanns were no strangers to CUAG, having loaned textiles and weaving pulleys to African Art from Ottawa Collections, an exhibition we presented in 1994. Our lack of experience installing textiles (none of the current staff worked here in 1994) did give us pause, as did our desire to maintain curatorial focus (we usually show contemporary Canadian art). But we knew the collection was of excellent quality, we acknowledged there’d been too little African content in our program, and we guessed (correctly) that such an exhibition would be of interest to Carleton’s dynamic new Institute of African Studies (IAS).

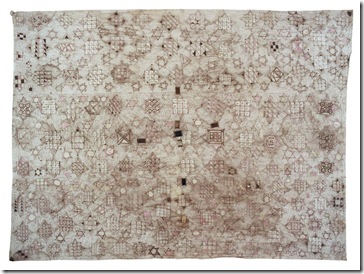

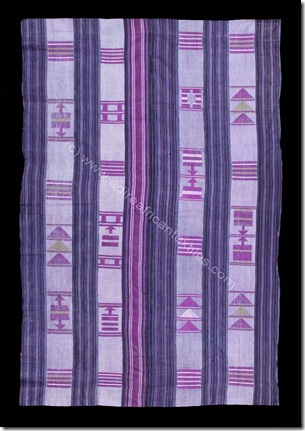

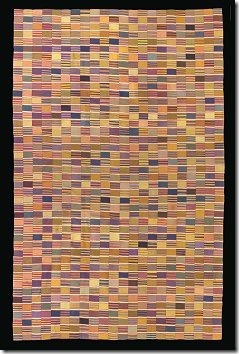

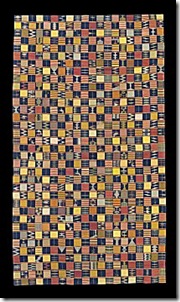

The first task was to find a guest curator. We are lucky in Ottawa, in that the city affords us a rich range of scholars and experts in many fields. But we’re always keen to tap Carleton talent and so, on the advice of IAS faculty member Ruth Phillips, we approached Catherine Hale, a Carleton graduate and current doctoral candidate in the History of Art and Architecture at Harvard University. Catherine, whose research focuses on the material culture of the Asante peoples of Ghana, accepted our proposal and soon began meeting with Barbara McCann to learn about the collection and over time, to select for presentation approximately 60 textiles from the more than 600 in the McCann collection.

The job of installation falls to the gallery staff. As the exhibition’s co-ordinator, I was preoccupied by the daunting challenge of mounting the textiles. We’re not the Canadian Museum of Civilization – we have a tiny staff; we don’t own mannequins or any specialized display furniture; and we rarely install works that fall outside the category of “fine art,” especially large, heavy and unstructured pieces of fabric. While in Seattle on a research trip in November, however, I saw a stunning textiles exhibition at the Burke Museum of Natural History and Culture. Their staff had invented an ingenious mounting system using standard-issue plumbing hardware that enabled them to “float” each textile off the wall. We couldn’t adapt the system to meet our needs, but it provided the seed of an eventual solution.

In December, I arranged for the transport to CUAG of Catherine’s selection of works from the McCann collection. Gallery technician Patrick Lacasse and I opened the storage containers after a 24-hour acclimatization period and examined each textile, discussing ways and means of installing it within the framework of Catherine’s curatorial vision. That first glimpse at the textiles was, for me, both exhilarating and intimidating; each work we unpacked was more wondrous than the one before it and we were anxious, as always, to accomplish the installation with utmost care and respect.

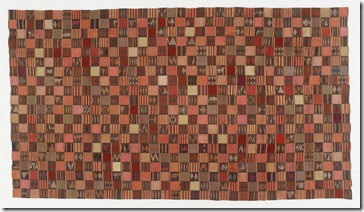

Conversation Pieces opened on Valentine’s Day and the exhibit ran until April 24.The show was dominated by three large montages that featured diverse textiles and articles of clothing that hung on dowels and suspended by wire from the ceiling, a mode of display Catherine saw as evoking the aesthetic of bustling African marketplaces. Other works were presented in wall-mounted and free-standing display cases, and on mannequins loaned by the Agnes Etherington Art Centre. The gallery space was completely transformed; visitor response to the collection and the installation has been overwhelmingly positive.

With the help of Catherine, Ruth Phillips and IAS Director Blair Rutherford, I planned a program of special events to accompany the exhibition. Pius Adesanmi, winner of the 2010 Penguin Prize for African Writing, delivered a lecture that seamlessly mixed the personal, political, theoretical, sartorial and musical (Pius was joined by his fellow Nigerians in the audience in impromptu performances of two songs). A lively panel discussion featured Catherine, Barbara McCann and textiles expert Lisa Aronson of Skidmore College in New York. Susan Vogel, founder of the Museum for African Art in New York City, came to Ottawa to screen her film Fold Crumple Crush: The Art of El Anatsui, which was followed by an illuminating discussion moderated by Adrian Harewood of CBC News Ottawa. And Barbara McCann gave tours of the exhibition to many interested community groups.

I won’t soon forget the morning Barbara first saw the installation, then in progress. She cried tears of joy. Her reaction was a harbinger of the success of the installation, exhibition, and public program, which demonstrated to me in a fresh way the risks and rewards of venturing into what was, for the gallery’s staff, terra incognita.

Sandra Dyck is the curator at the Carleton University Art Gallery”

Reproduced from: “Carleton Now”

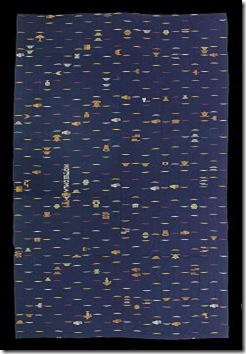

“Power and Prestige wall.” photo copyright Barbara McCann, please do not reproduce without permission. Click for a larger view.