“An exhibition of the African artistic abilities that transform natural materials such as cloth and clay into spectacular artifacts will open on Monday, Feb. 28, in Dowd Gallery at SUNY Cortland.

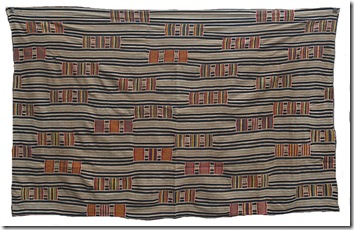

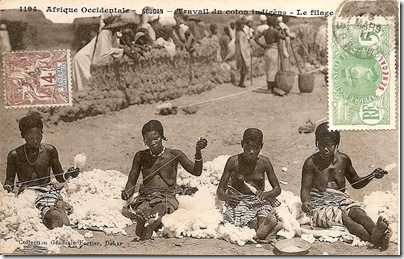

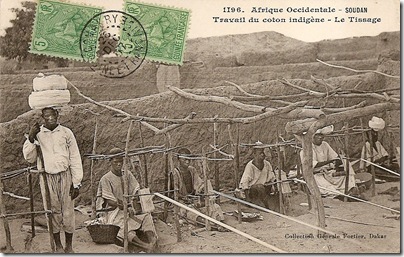

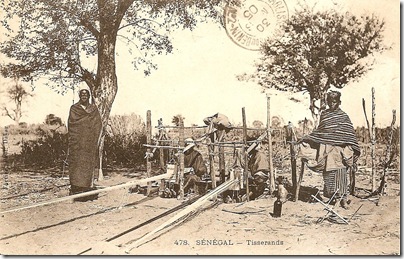

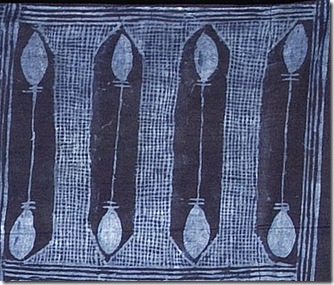

"Bògòlanfini, Patterns of Bamana Culture," an exhibit that explores authentic mudcloth methods practiced by people belonging to Bamana Culture in Mali, Africa, is from the personal collection of Kassim Kone, professor of anthropology and linguistics at SUNY Cortland.

An opening reception will take place the same day beginning at 5 p.m. at Dowd Gallery. The event, which is free and open to the public, will be enhanced by a dance performance by the Africana Dance Ensemble. Refreshments will be served.

Three lectures will accompany the exhibit, which runs through Monday, April 18:

• Barbara Hoffman, associate professor in the Anthropology Department at Cleveland State University, Cleveland, Ohio, will speak beginning at 5 p.m. on Tuesday, March 8;

• Tavy Aherne, visiting professor and art historian from DePauw University in Greencastle, Ind., will present at 5 p.m. on Thursday, March 31; and

• Kone will discuss his collection at 4:30 p.m. on Wednesday, April 6.

All lectures will be in the Dowd Gallery and are free and open to the public.

The project represents a collaboration between Kone and Dowd Gallery Guest Curator Jenn McNamara, assistant professor of fibers in the College's Art and Art History Department.

"In Bamanakan, bogo means clay or mud, lan by the means of, and fini or finis means cloth," explained McNamara. "Choosing the work for this show was rather difficult given so many beautiful examples. In the end, the exhibit is arranged so the viewer may see the wide variety of functions the mudcloth serves: initiation ceremonies, hunting garb, symbology and storytelling as well as the appearance of global influences on the cloth. Each symbol incorporated in the design has a specific meaning and importance."

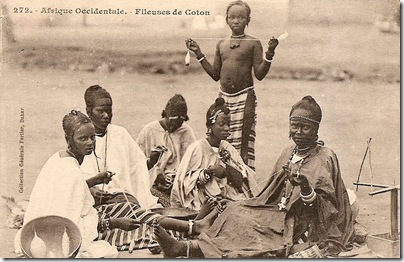

Many local women have studied this technique, dedicating their lives to introducing the craft to the world beyond African borders.

"The renowned artist Nakunte Jara, whose work has been on permanent display at the Smithsonian, created many of the mudcloths in Kassim's collection that are included in the exhibition," McNamara said.

"The mud dyeing technique not only reflects a long history and cultural integrity but has also become a tool to propel Mali's cultural future and its place in the contemporary world," McNamara explained.

The most recent high profile use of mudcloth was its inclusion in the RED product line launched by U2's Bono and Bobby Shriver in 2006 when Converse chose to make Chuck Taylor shoes from mudcloth. This highly publicized event began in Davos, Switzerland, at the World Economic Forum and culminated at the Oprah Winfrey and Larry King Shows in the U.S. Kone was the anthropologist hired to purchase the mudcloth for Bono's RED-Converse mudcloth Chuck Taylor shoe project.

Kone grew up in the Beledugu region, believed to be the heart of Mali's mudcloth art.

"Bògòlan is a very important component of Bamana culture as this cloth is an essential part of most Bamana initiation and ritual events," Kone said. "I began to research bògòlan at a very early age when I worked as a research assistant to many American doctoral students. I began to collect mudcloth when I was in college. No two pieces are the same, even when dyed by the same artist. This explains why over the course of many years I have amassed a significant collection of mudcloths."”