shared from Ghana Business News

“Batakari has spoken, who needs a suit?

From Fufulso towards Fulaniland

Fugu is king

Batakari has spoken, who needs a suit?”

The fugu smock is the most distinctive dress from Northern Ghana. The striking garment dates way back but the way men and women drape it in recent times reflect style and modernism. Also known in southern Ghana as batakari, fugu has evolved from a native wear to a recognisable fashion statement awaiting its turn at the international catwalk.

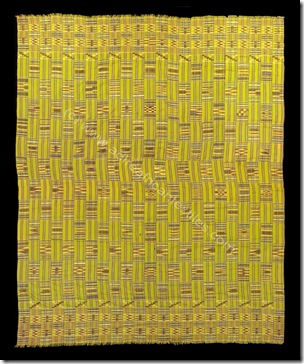

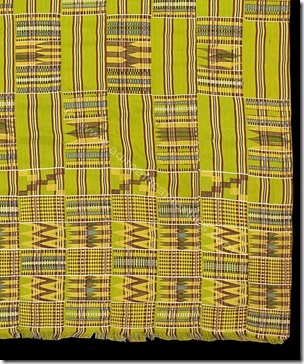

Fugu is a practical dress which provides protection for the body against both heat and cold. Compared to the kente fabric native to the Ashanti and Volta Regions, fugu is much rougher and a little less colourful. But its attractiveness and ready to-use mode makes it a must-have in everybody’s wadrobe.

Typically, the fugu gown is round necked, with short sleeves that have a rather wide opening. The smock is a plaid garment that is similar to joromi or the danshiki which originates from Nigeria. From the waist on, the dress spreads in a funnel shape sometimes reaching ankle length. The beauty of this shape is seen when men do the damba dance with the edge of the smock going round in circles.

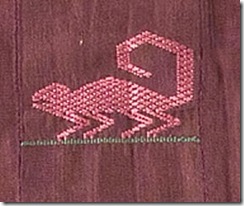

The fugu smock usually has embroidery on the neckline with a small V-cut above the chest. It has two hidden pockets which, but for the embroidery will be hidden.

Unlike the kente cloth, the boubou or the Japanese kimono which are all traditional wears for special occasions, fugu is an everyday garb. Because it hangs loosely it is easy to wear and work with, while offering grace to the wearer.

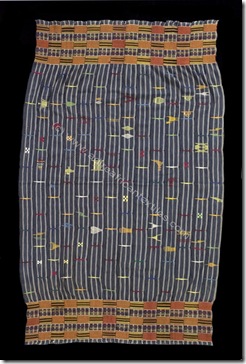

The fugu fabric is made from cotton which is processed into threads by women, dyed and then woven into strips or stoles. The strips are about four inches wide and their thickness depends on the number of threads used. The weaving takes place in simple hand looms. To make clothes, a collection of strips are sewn together. This may be machine sewn or hand made.

Not all fugu fabrics are the same. For instance, there is the plain calico type which originates from the Upper West Region. In a way, this contrasts with the thicker, multi-colour patterned ones from Daboya in the Gonja area of the Northern Region.

The fugu smock is easily adaptable. Apart from the typical design described above, there are other variations which are more or less elaborate. A simplified version is the tight-fitting, almost-sleeveless one that reaches the waist. A related variation also flows up to the waist but without ending in the skirt-shape.

In contrast, there are the more elaborate styles such as those which come complete with the fugu smock itself, a covering gown and a pair of drawstring trousers all in the fabric. The trousers or pantalon have an exaggerated pouch between the legs. To top it up, there is a cap also in fugu. You may call this the fugu three-piece. It is usually worn by chiefs on ceremonial occasions.

It could be said that it is in the women’s domain that much of the innovations of fugu is realised. Women look trendy in the traditional smock design. They wear this with a pair of shorts or knickers sewn with the fabric. Then there is the fugu blouse which is worn over a cloth tied round the lower half of the female shape. On another level, it is fashionable for females to use the fugu material for kaba and slit. Finally, fugu can be made into one flowing dress from the shoulders to the heels. Of course, trust our ladies to crown each of these styles with a piece of fugu as head gear.

In Ghana, the fugu smock assumed great significance when President Nkrumah chose to wear it in declaring Ghana’s independence. Indeed, a look at the dais on the historic moment of 6th March 1957 would show that all his aides were in fugu. It would be naive for anyone to think that the dress code for that grand occasion was for nothing.

When the fugu dress is worn the wearer conveys a sense of conservatism and equality. Fugu looks good on both men and women just as it does for the young the old. The smock is also the mode of dress for both rich and poor.

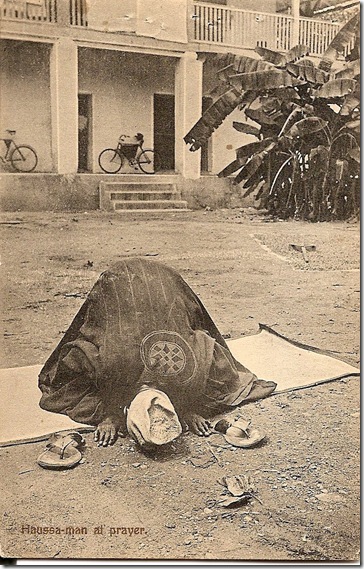

Adopting the fugu conveys an ability to co-exist. It is a dress for all. Christians wear it. Muslims wear it. Traditionalists, too, wear it. In terms of occasions, it can be worn practically for any social event. In fact, in Ghanaian society it is about the only attire that can pass for formal as well as casual. For some men, there is nothing more attractive than wearing the smock over a neatly worn shirt and tie.

That the fugu fabric lasts long is without a shred of doubt. In fact, a piece of fugu cloth can be worn for life. Curiosly, as the fabric ages, it assumes one attractive phase to another. For some, the older and jaded the smock gets the more they value it. This is especially true for the elderly. When old folks say ‘my fugu has seen more tatters than yours’ it means that they are older and thus have had more of life’s experiences. In truth, one mustn’t be surprised by this attitude of cherishing a worn out piece of clothing. The practice is only similar to how the youth adore and flaunt worn-out jeans. It is the same old vibe.

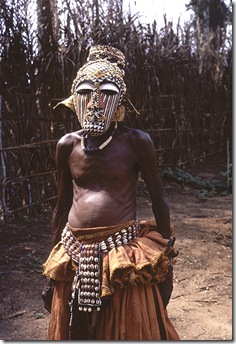

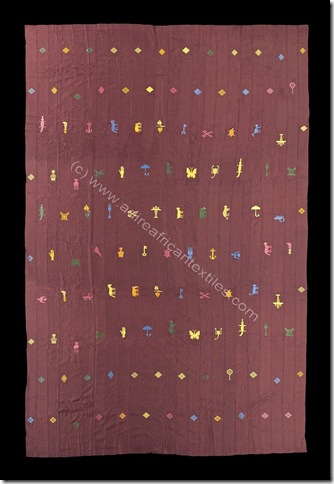

On a more serious note, fugu is not just a piece of garment. The cloth serves as the backdrop for expressing communal codes. It is also one of the items that embodies traditional values. Often, symbolic patterns are embossed on the front and back. Common examples of these motifs are the heart or stars. Lately, ‘foreign’ concepts such as adinkra symbols are fitted in. It must also be noted that there is currently an introduction of brighter colours other than the traditional shades of blue, black and white.

Among the Dagaabas of the Upper West Region, the dress is known as ‘Dagarkparlo’ meaning ‘a Dagarti man’s wear.’ For Northern Chiefs, fugu is a mandatory costume. To some extent, the smock or batakari is also seen as a war dress. In this regard, it is adorned with protective amulets. For a man’s last respect, he is laid in state dressed in fugu. He is also buried in it.

Fugu, today, has become the basis for a vibrant traditional textile industry across Northern Ghana. From Bolgatanga through Tamale to Daboya young people, especially are actively producing to meet growing demand. The industry revolves around dyeing, weaving, sewing and designing.

Beyond Ghana, people of African descent are also taking a liking to fugu. Perhaps, in portrayal of Nkrumah’s ‘African Personality,’ many wear the Northern Ghana smock in America, Europe and the Caribbeans. Fugu is beautiful, modest and flamboyant. The good news is that it does not appear that it will be disappearing into history any moment soon.

By Kofi Akpabli